Had you worked with this composer [Jorane] before?

No. I’m always seeking collaboration as the genesis of a project. I’m interested in changing my creative process with each new collaborator. Historically, I have mostly done that through collaborations with music—bands, composers, new iterations of a classical score. But here, the visual art component was the primary partner, so I couldn’t even think about music until we really knew what we were doing. Last summer we were in Montreal, and I was sourcing all this music. Then someone came to our showing in Montreal and connected us with Jorane, who has composed for dance and film. I listened to her entire oeuvre. She works with electronically mixed cello and voice and has a broad range. Here at PS21, she will perform with us live. But eventually, our goal is to have both options for a presenter—either with a live performer or a recording.

So is she composing around your work?

It’s been both. We met in January to design our working process. At first, she watched our performance video. Then I sent her videos of individual sections, and she mapped music to those choreographed sections. So it has been a back and forth process.

Let’s talk about another aspect of what you are doing at PS21—the Pathways Workshop. Are you doing this kind of community-based programming elsewhere? Can you tell us more about it?

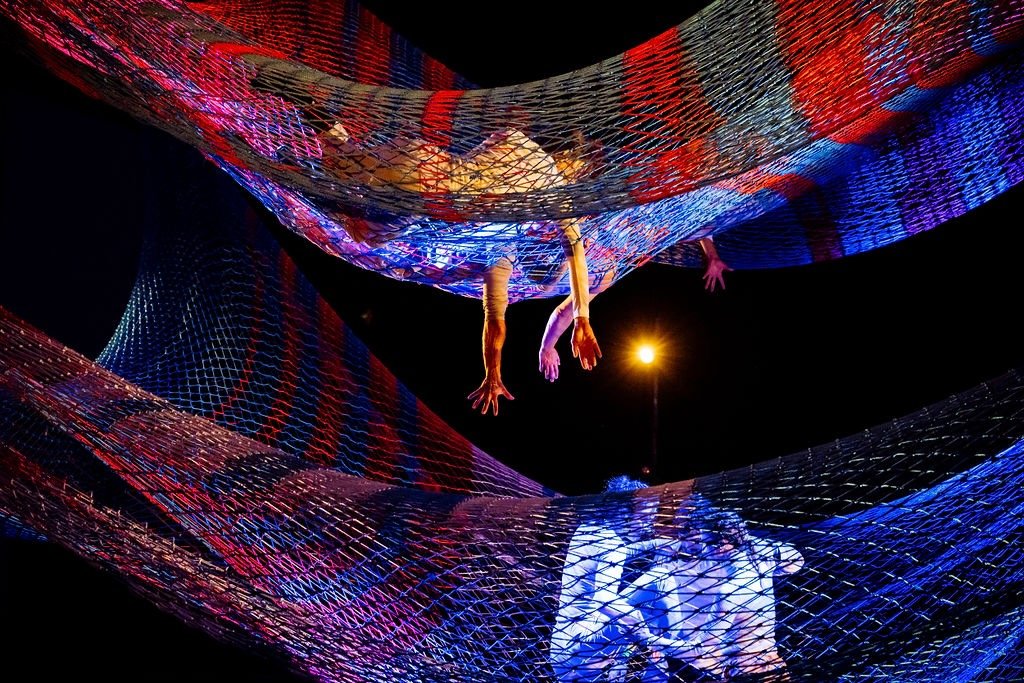

Developing the pedagogy and structures around this workshop are a key part of the process and progress of this piece. Because of the many open workshops we’ve had with university students, we are aware that when you feel the environment of the net, it changes how you feel about the world. It makes tangible the physicality and emotional entwinement with everything around us.

It is very important to have a clear pedagogy about bringing people into the net safely. The Pathways Program was the first time we codified a progression of how to take people onto the net alone, how to introduce a partner to the equation so that they can move across this environment together with all its implications. First, we started under the net—to feel the forces, the rebound, and the understanding that this is not just an apparatus, but a conversation with an artwork. You are dancing with a sculpture—not just a rope. This sculpture is an embodiment of its own thing. We take the time for people to have a felt experience of their impact on something larger.

This fall, we will be in residence at MIT, where we will be working with disability consultants and organizations to create specific workshops for disabled people as well as able-bodied people. When we were working in Nova Scotia, an artist who uses a wheelchair came to one of our workshops and shared, “Being in the net is what I experience daily life to be.” She hopes that we can offer this experience more broadly.

What kinds of tasks or challenges do you give to participants in your public workshops?

We start with a roll. Then we try to make the net still. We do a sit-to-stand. Next, we work on balancing variations taking two limbs off the net. Then we do a partnered walk and, finally, a swing.

The comments were incredible. What people said confirmed our hopes. Some said that everyone should have to move through the net before seeing the piece. The dancers always say, “Walking in the net is the hardest thing.” It may be the most basic, but it is also the hardest. We task participants with a solo walk through the net. Afterwards, the company members demonstrate how doing it with a partner multiplies the challenge. The big thing that resonates with the dancers is that you must connect with yourself first. You can’t help someone else until you have achieved stability. Only then can you work together to find that shared effort to fulfill the task. Even when you are just walking in a shared weight situation, with every micro-movement in taking a step forward, everything changes. You have to keep connecting with yourself to balance through those changes.

comments