Successfully pulling off either of these scenarios means producing something akin to a novella—a full-bodied offering that delves into detail without wearing out its welcome. Wayne McGregor’s “Entity” is just that. The contemporary work, created in 2008 and recently restaged at London’s Laban Theatre, unfolds efficiently and with depth, marrying the visceral and the calculated. Created in service of a research project on choreography and artificial intelligence, it fits neatly into McGregor’s broader oeuvre, in which the sciences are frequently mined for artistic inspiration.

The show opens and closes with a clip of a running dog projected onto one of three large panels framing the stage—a fitting bookend to its fast-moving pace and nervy mood. The action plays out over two diverse musical strains—a flowing strings composition from Joby Talbot followed by an edgy electronica score from Jon Hopkins—both of which fluidly accommodate wave after wave of signature McGregor choreography, a tangle of strange shapes, sharp lines and glossy incisions through space. The nine dancers, clad in simple white tanks and black briefs, don’t inhabit discernible characters, but visible displays of emotion bubble up in their various groupings: combative trios, inquisitive duets, whole-cast sequences conveying affection and neediness.

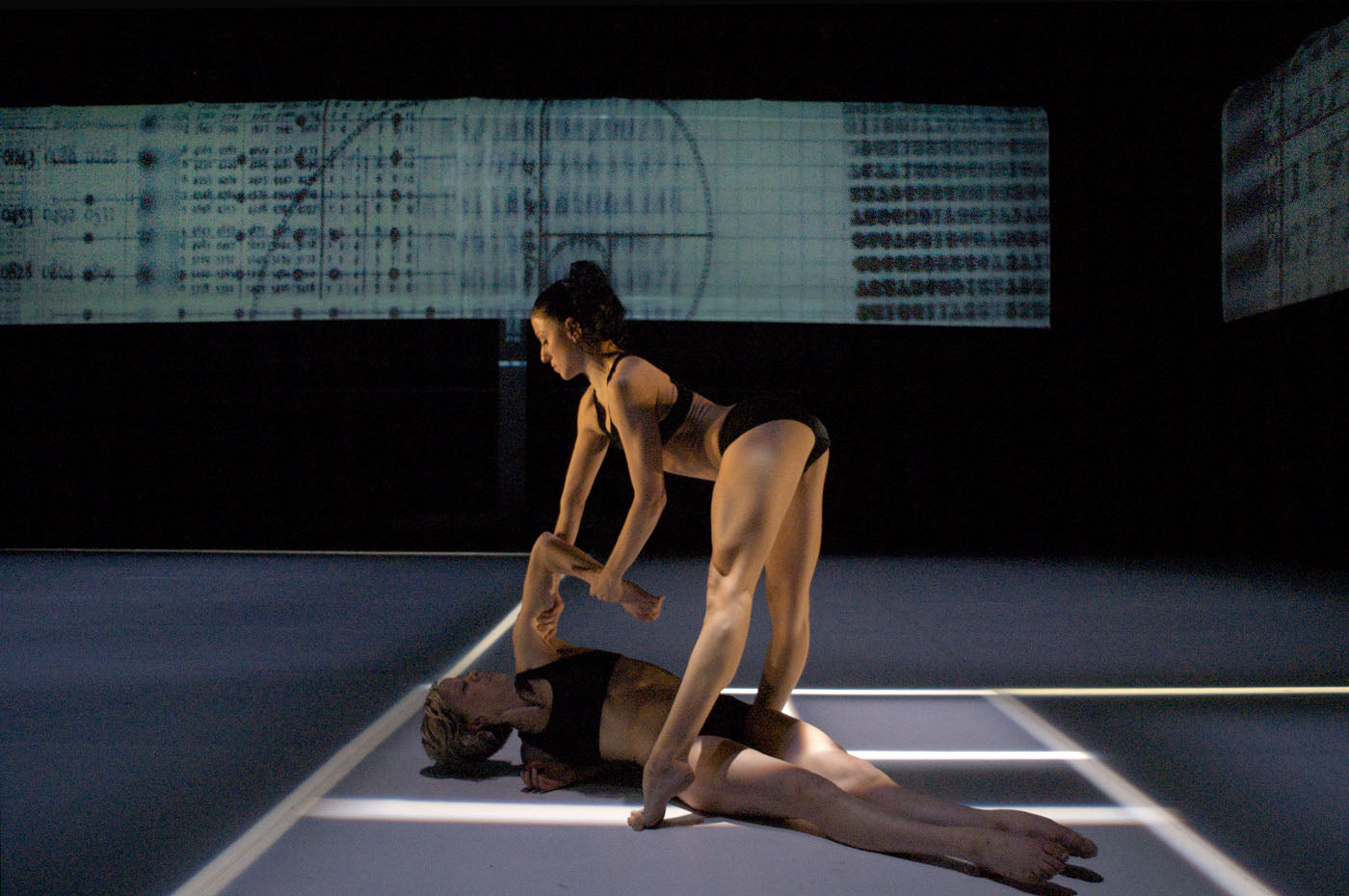

Rather than parsing out a narrative or even a particular theme, “Entity” busies itself with maintaining a physical tension, a taut strum of energy that underpins every motion, regardless of its tempo. Purposeful marching, forceful scissor-kicks, firm torsos and brisk extensions are all bundled into a skein of clambering falls and sleek recoveries. In one scene, a woman thrusts against the force of the two men carrying her, clenching as they lift her in a plank position and drag her across the floor. The interaction might seem violent were her resistance not so perfectly foiled to their manipulations, a neat yin and yang of push and pull.

At times the choreography slips from stylishly disarrayed to outright disorganised, especially when multiple groups perform different sequences at the same time; but for all its tumult, it rarely jars—a testament to McGregor’s eye for phrasing as well as the dancers’ polished articulation. A focus on extremity—whereby natural movements are cranked into their superlative, with twists wrenched into coils and reaches catapulted into grasps—quickly emerges as a staple of the movement vocabulary, as does an animalistic mien, manifest in leonine struts, spidery walks, crepuscular crawling. This creaturely aesthetic is amped up in a late segment featuring a soundscape of primordial gloops and clicks, the four women of the piece sprawling under ghostly green light. Later two men circle and lunge at each other, peacocking like birds fighting over a mate.

The uber-fit cast make for a formidable bunch, particularly when their tops come off halfway through, unveiling a mass of brawn and sinew. Many have high-level ballet training, and all boast excellent flexibility, particularly Po-Lin Tung, a 2016 company joiner tasked with some of the show’s most demanding contortions. Jessica Wright, one of only two original cast members in this restaging, shone as one of the most rock-steady in the face of breakneck tumbles, while Fukiko Takase too proved deft at making the punishing appear easy.

After some 50 minutes of furious hotfooting, the dancers’ energy levels sagged a smidge, but they permitted little slack in tension in the final minutes. As far as an hour of dance goes, they rarely come more potent than this.

comments