Talent Time

It’s “Nutcracker” season at San Francisco Ballet—36 performances packed into three weeks—which means that the company is currently serving two distinct audiences.

Continue Reading

World-class review of ballet and dance.

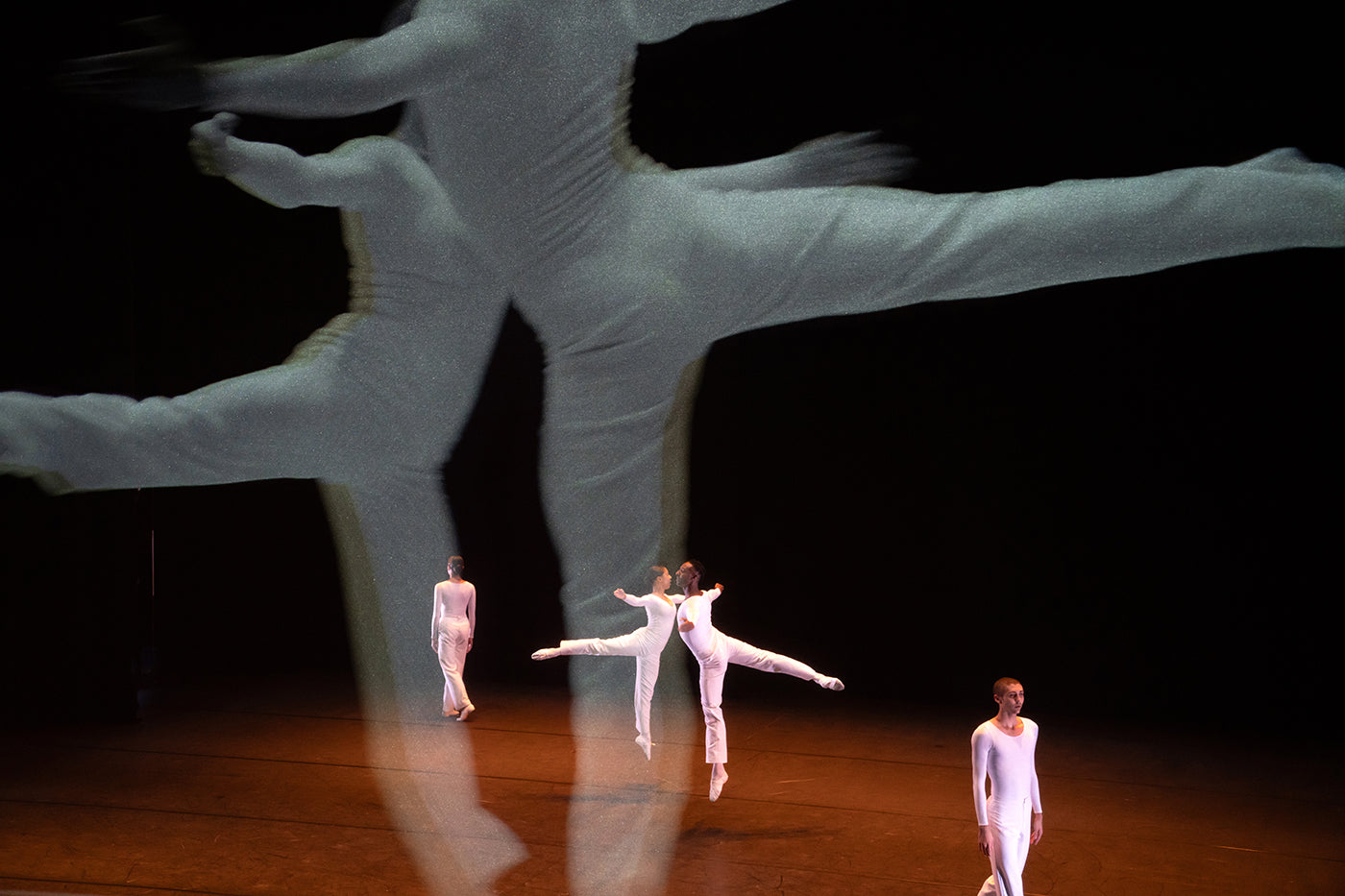

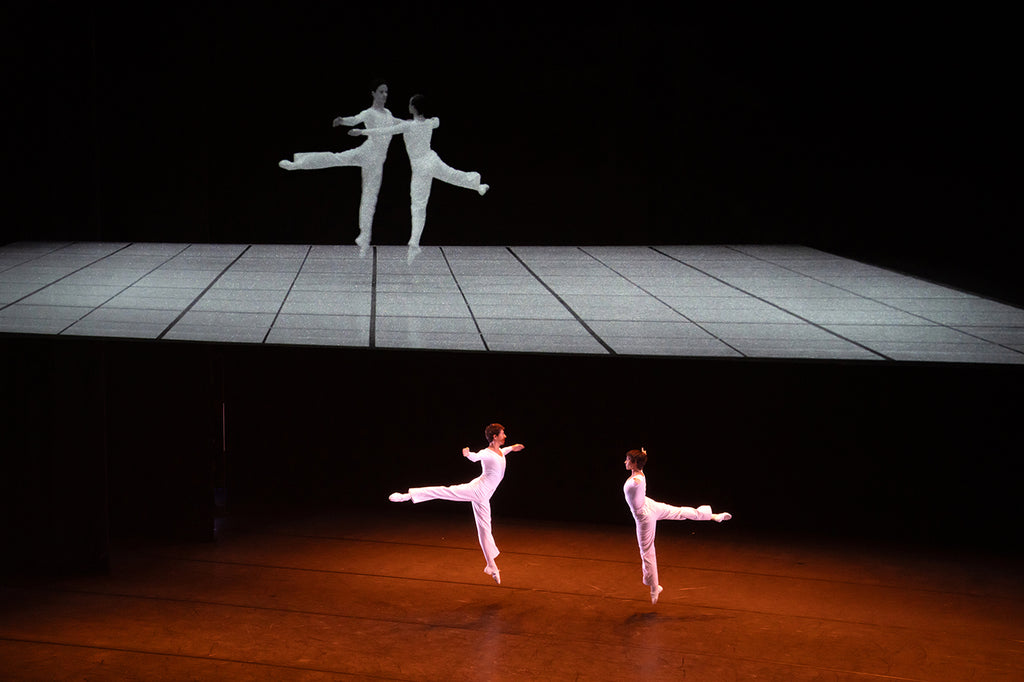

What is dance?” is a question posited by postmodern choreography, and postmodern choreographers generally seek to answer it through means as far away from conventional notions of dance as possible. Classical codifications are often eschewed, along with formal training and any vestiges of performativity—including music, costumes, makeup, sets, lighting, and stages. Process is prized over product. Practitioners of the Judson Dance Theater, who formed the postmodern dance movement in Greenwich Village in the early 1960’s, frequently sought out pedestrians and tasked them with mundane activities like squeezing oranges or reciting addresses. Choreographer Lucinda Childs emerged from this scene. In a 1964 solo she made for herself, she sat on a stool with a colander on her head and stuffed her mouth with hair rollers and kitchen sponges.

Performance

Place

Words

“Uncommonly intelligent, substantial coverage.”

Your weekly source for world-class dance reviews, interviews, articles, and more.

Already a paid subscriber? Login

It’s “Nutcracker” season at San Francisco Ballet—36 performances packed into three weeks—which means that the company is currently serving two distinct audiences.

Continue ReadingLast week I caught up with choreographer Pam Tanowitz and Opera Philadelphia’s current general director and president, countertenor Anthony Roth Costanzo to talk about “The Seasons,” the company’s latest production premiering at the Kimmel Center’s 600-plus seat Perelman Theater on December 19.

Continue ReadingIf Notre-Dame remains one of the enduring symbols of Paris, standing at the city’s heart in all its beauty, much of the credit belongs to Victor Hugo.

Continue ReadingWhen dancer and choreographer Marla Phelan was a kid, she wanted to be an astronaut. “I always loved science and astronomy,” Phelan said.

Continue Reading

comments