Heartfelt Moments

The Australian Ballet’s “Signature Works,” as a whole, is a compact and varied celebration of dance in the moment.

Plus

World-class review of ballet and dance.

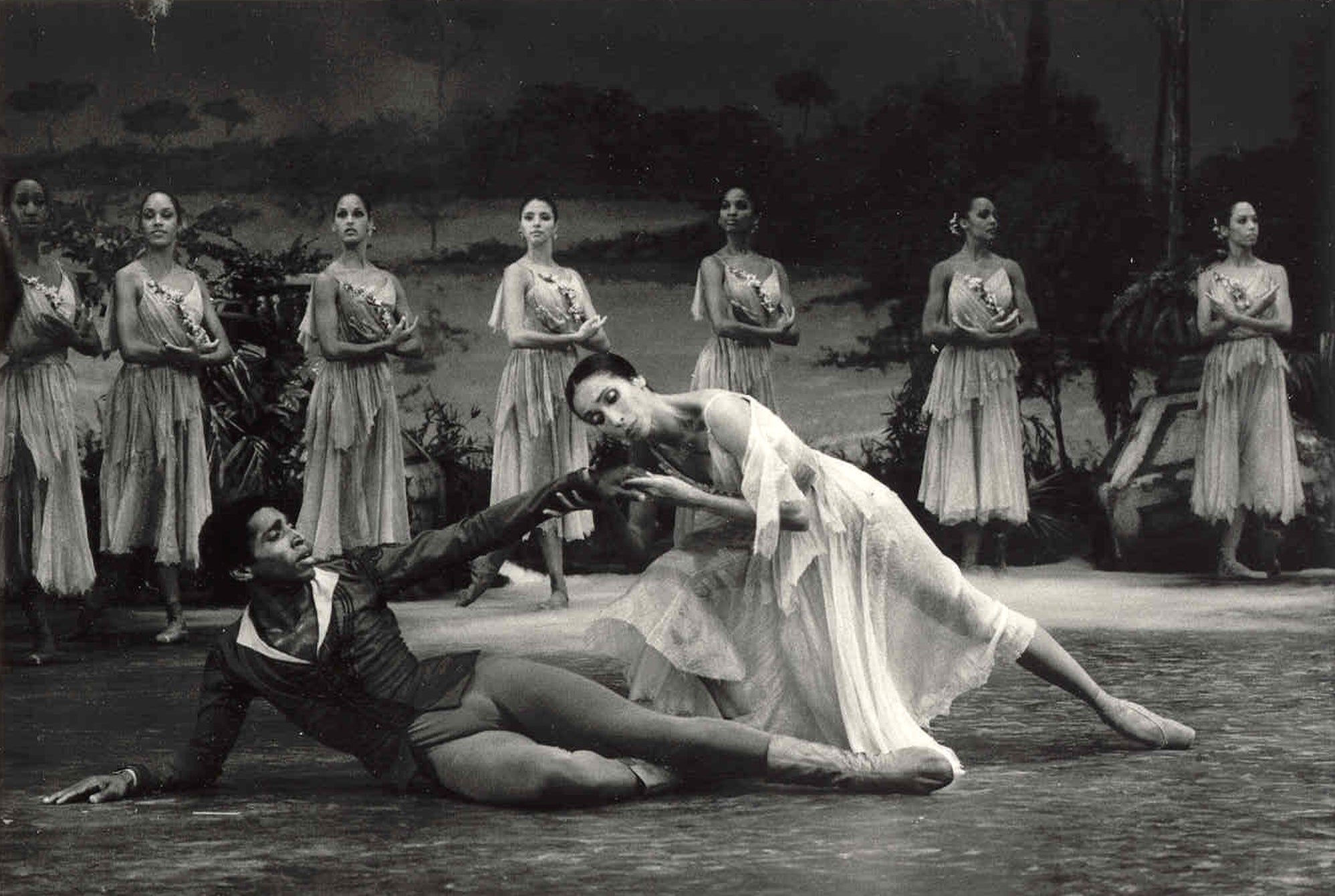

For thirteen years, from 2011 until this summer of 2023, Virginia Johnson was Dance Theatre of Harlem’s artistic director. She began her tenure before there was even a company to direct. In 2004 the ensemble that she joined in 1969, the year Arthur Mitchell formed the company, had been forced to go on hiatus because of serious financial problems. The question of whether it would get back on its feet was a real and agonizing one. And then in 2010, Mitchell, her mentor, asked her to lead the effort to bring it back. It was not a project she had sought out, or that she craved. But it was impossible not to accept the challenge. The company, which Mitchell had created in response to Martin Luther King’s assassination, was too important not to save.

“Uncommonly intelligent, substantial coverage.”

Your weekly source for world-class dance reviews, interviews, articles, and more.

Already a paid subscriber? Login

The Australian Ballet’s “Signature Works,” as a whole, is a compact and varied celebration of dance in the moment.

PlusThe Joffrey Ballet’s lithe and strong dancers take on four historic works in this mixed-bill “American Icons” programme.

PlusIn Trisha Brown's 1983 “Set and Reset,” dancers float in and out of the wings like bubbles.

PlusTalk about perfection! While the countdown is on, as Gustavo Dudamel, music director of the world-class Los Angeles Philharmonic, prepares to exit the stage for the New York Philharmonic (a big boohoo), his presence last weekend at Walt Disney Concert Hall further cemented his status as musical genius, tastemaker and catalyst for good.

Plus

comments