The Two of Us

When I think of the desert, the first impression that comes to mind if of unrelenting heat, stark shadows, the solitude of vast space, occasional winds, and slowness.

Plus

World-class review of ballet and dance.

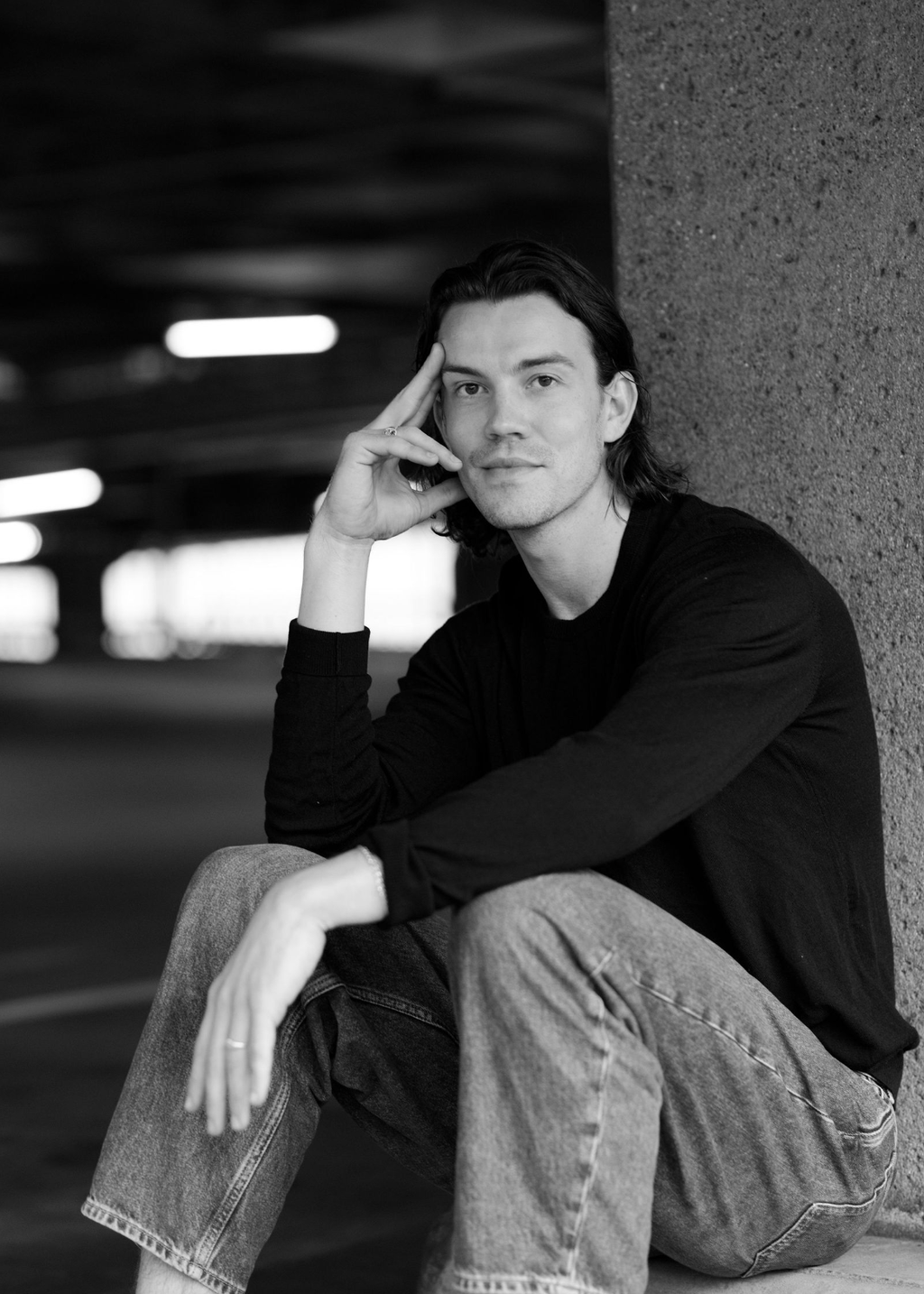

Like the productions he creates, Jack Lister is three things: enigmatic, polished, and intentional. He is both artist and observer, subject and spectator; his innate polarity creates a unique, yet candidly earnest, profile. For Brisbane audiences, Lister is a known secret. His transition from company dancer to choreographer has had a steady but tangible impact on the local mainstage. Now, as Associate Artistic Director of Australasian Dance Collective, this impact has the potential to be tenfold—an increase that would be both readily welcomed and well-earned.

“Uncommonly intelligent, substantial coverage.”

Your weekly source for world-class dance reviews, interviews, articles, and more.

Already a paid subscriber? Login

When I think of the desert, the first impression that comes to mind if of unrelenting heat, stark shadows, the solitude of vast space, occasional winds, and slowness.

PlusTwo works, separated by a turn of the century. One, the final collaboration between Bill T. Jones and Arnie Zane; the other, made 25 years after Zane’s death.

PlusLast December, two works presented at Réplika Teatro in Madrid (Lucía Marote’s “La carne del mundo” and Clara Pampyn’s “La intérprete”) offered different but resonant meditations on embodiment, through memory and identity.

PlusIn a world where Tchaikovsky meets Hans Christian Andersen, circus meets dance, ducks transform and hook-up with swans, and of course a different outcome emerges.

Plus

comments