Mishima’s Muse

Japan Society’s Yukio Mishima centennial series culminated with “Mishima’s Muse – Noh Theater,” which was actually three programs of traditional noh works that Japanese author Yukio Mishima adapted into modern plays.

Plus

World-class review of ballet and dance.

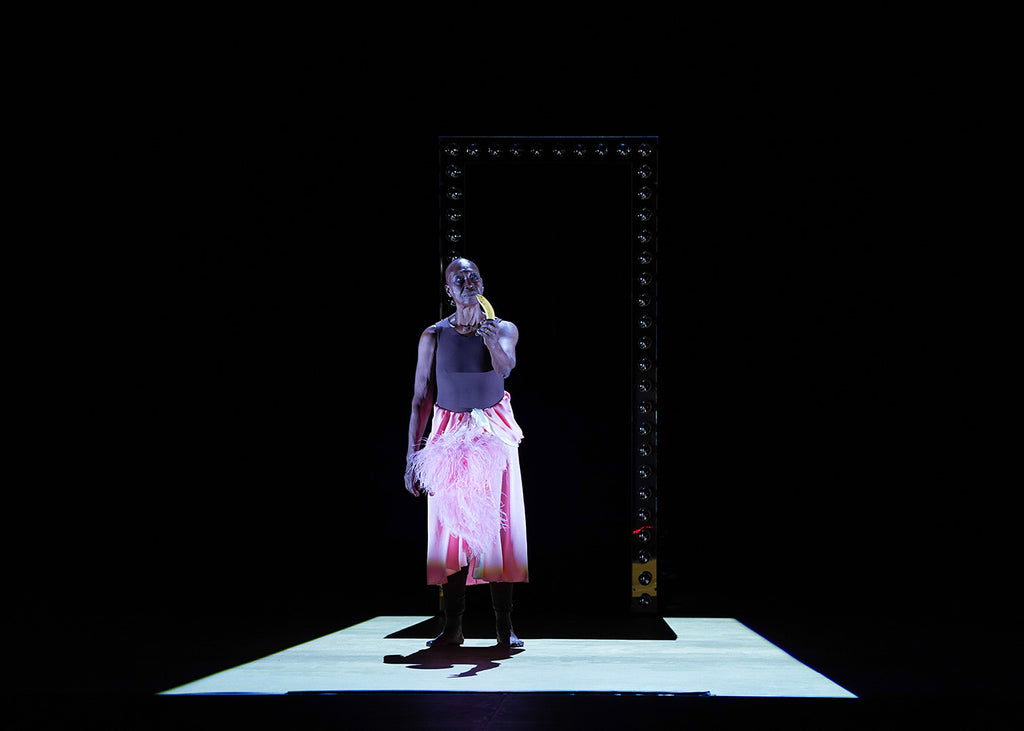

It will be impossible to walk past the Panthéon again without recalling what happened at the Théâtre des Champs-Élysées in late September 2025: the extraordinary transformation—verging on possession—of Germaine Acogny into Joséphine Baker. Madame Baker, the celebrated artist and member of the French Resistance in World War II, is buried in Monaco. Since 2021, however, she has been honoured at the Panthéon with a cenotaph—a symbolic tribute to her artistry, her resistance, and her civil-rights activism. Acogny brought her back to life just a few arrondissements away, on the very stage where Baker had made her Paris debut in “La Revue Nègre”—a sensation in 1925.

Performance

Place

Words

“Uncommonly intelligent, substantial coverage.”

Your weekly source for world-class dance reviews, interviews, articles, and more.

Already a paid subscriber? Login

Japan Society’s Yukio Mishima centennial series culminated with “Mishima’s Muse – Noh Theater,” which was actually three programs of traditional noh works that Japanese author Yukio Mishima adapted into modern plays.

PlusThroughout the year, our critics attend hundreds of dance performances, whether onsite, outdoors, or on the proscenium stage, around the world.

PlusOn December 11th, the Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater presented two premieres and two dances that had premiered just a week prior.

PlusThe “Contrastes” evening is one of the Paris Opéra Ballet’s increasingly frequent ventures into non-classical choreographic territory.

Plus

comments