Acogny’s creation, conceived with her longtime collaborator Alesandra Seutin, was more than homage: it was a meeting of trajectories. The choreography triangulated between Baker’s exuberant rhythms, Acogny’s contemporary vocabulary, and their shared African heritage. Fabrice Bouillon-LaForest’s score echoed this fusion, interlacing Charleston riffs with African sonorities and producing—like the choreography—something strikingly new and elusive. Mikaël Serre’s drums set the pulse, punctuated by Baker’s own words: fragments of interviews, speeches, memoirs. The text began with accusations of Baker as a ‘devil,’ moved through her famous declaration ‘ni juifs, ni chinois, ni nègres’, and culminated in the simple affirmation: ‘I am Josephine Baker.’

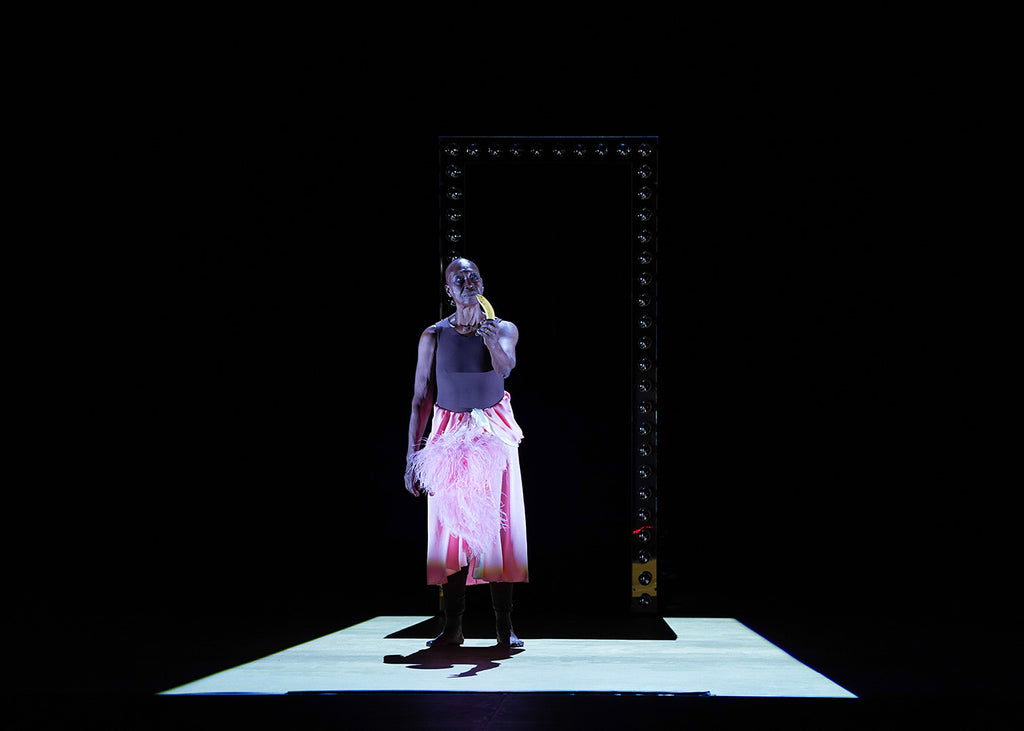

“Joséphine” unfolded like a ritual of invocation, its talisman an Ashanti doll that remained on stage throughout—a medium channelling Baker’s presence. The opening image was unforgettable: a silhouette in a black dress with flowers on the back, one arm casting a hypnotic shadow against the Théâtre’s monumental golden curtain. As the curtain shifted, the scenography revealed itself, pared down to essentials. On the otherwise empty black stage stood a full-scale light-bulb frame—the mirror itself missing: an emblem of absence, an evoked reflection. With extraordinary magnetism, Acogny lit up the darkened stage. She cycled through costumes that conveyed authorship rather than mimicry: first a pink feathered dressing gown, then a lean costume with a green belt amplifying the movement of her hips.

At one point, a banana appeared from the frame and was placed in her hands. With this symbol she recast Baker’s scandalous ‘banana dance,’ once performed for Parisians in little more than a skirt of sixteen rubber bananas—a provocation that toyed with stereotypes of race, exoticism, empire, and gender, unsettling French colonial fantasies. Acogny used the fruit subversively: she hurled it at the audience. Laughter rippled at first but quickly subsided under her unflinching gaze. Unease gave way to silence, then reflection. As the dance turned inward, Acogny walked solemnly in military attire while Baker’s voice re-emerged—an excerpt of her 1963 Washington speech, evoking the deep injustices of racism in the USA. In thirty minutes, Acogny honoured Baker’s life trajectory: her rise from poverty in St. Louis to international fame in Paris, her role as a Resistance spy, and her adoption of a ‘rainbow tribe’ of children. Baker was here not nostalgically commemorated but reactivated: her values—freedom, equality, embodied resistance—brought urgently into the present.

Despite Acogny’s magnetism and the symbolic weight of the work, the solo itself occasionally felt static, even a little flat. Its dramaturgy, centred so entirely on her figure, might have gained breadth through the presence of other performers. Yet the audience responded with clear enthusiasm—a reaction owing as much to the symbolic charge of the piece as to its choreographic invention.

comments