Talent Time

It’s “Nutcracker” season at San Francisco Ballet—36 performances packed into three weeks—which means that the company is currently serving two distinct audiences.

Continue Reading

World-class review of ballet and dance.

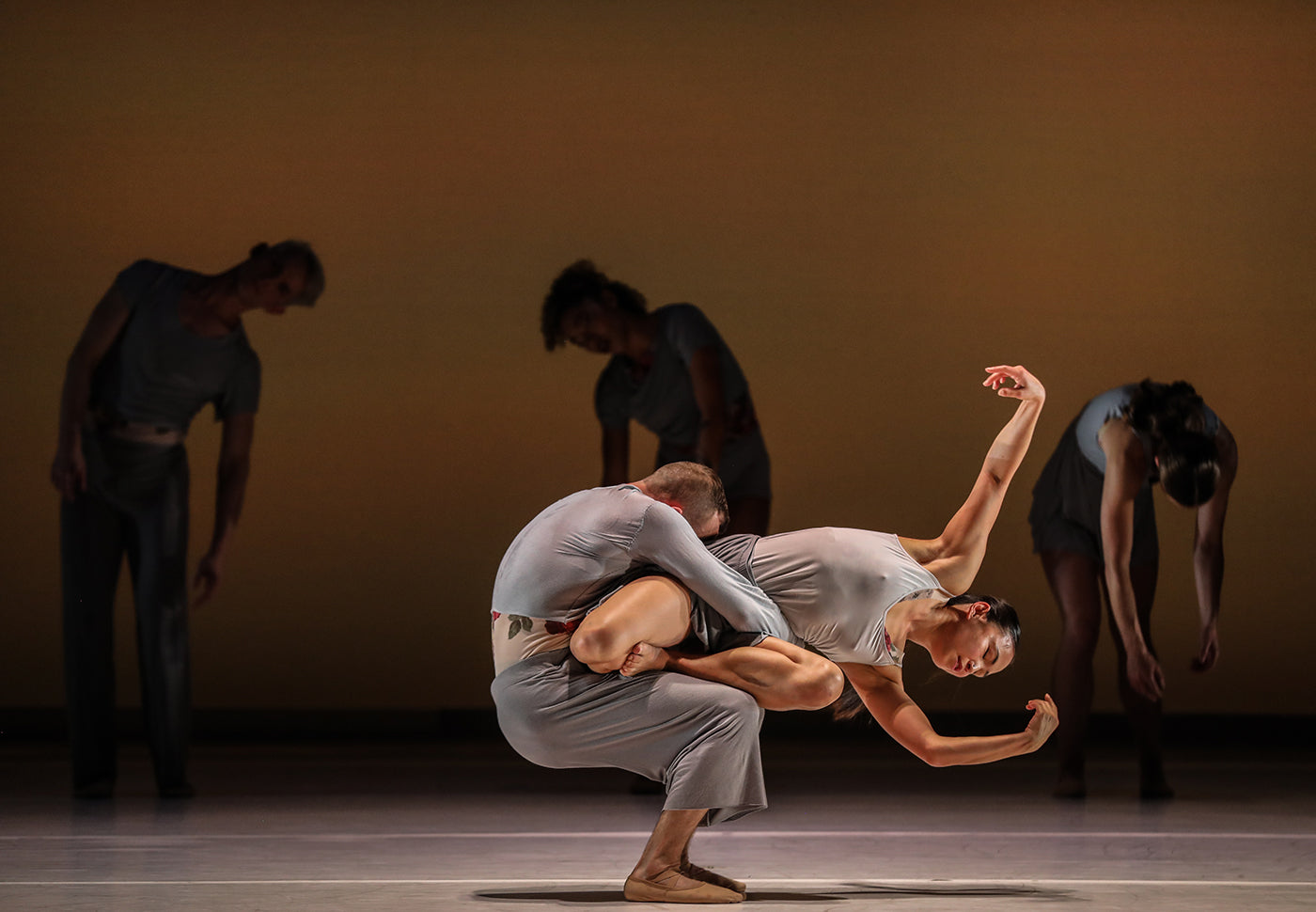

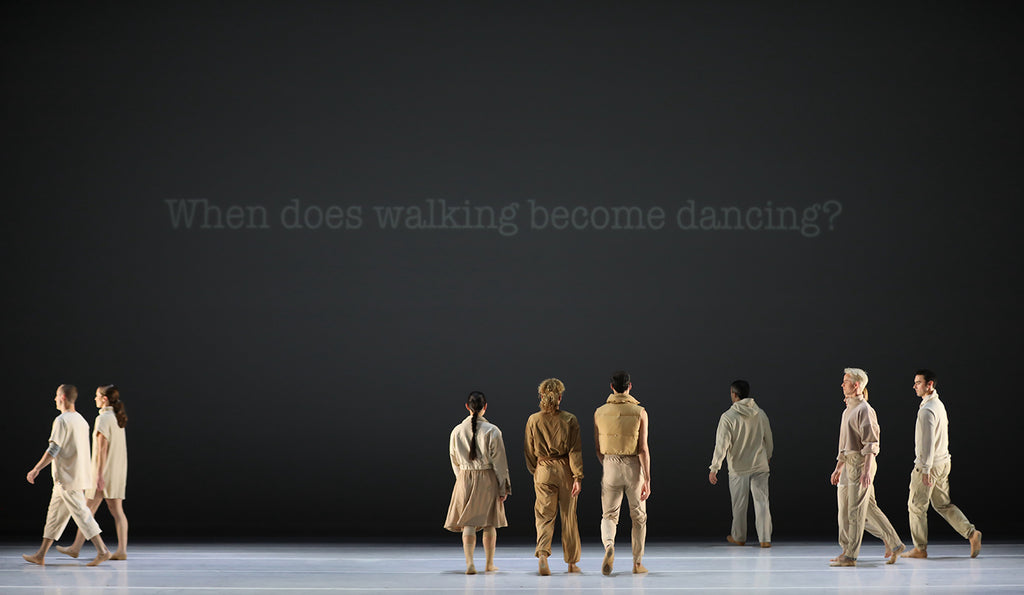

One might easily mistake the prevailing mood as light-hearted, heading into intermission after two premieres by Brenda Way and Kimi Okada for ODC/Dance’s annual Dance Downtown season. Maybe this is just what we need to counter world events, you may think. But there is much more to consider beneath the high production values of this beautifully wrought program. Okada, for instance, folds a dark message into her cartoon inspired “Inkwell.” And KT Nelson’s “Dead Reckoning” from 2015 reminds us the outlook for climate change looms ever large.

Performance

Place

Words

“Uncommonly intelligent, substantial coverage.”

Your weekly source for world-class dance reviews, interviews, articles, and more.

Already a paid subscriber? Login

It’s “Nutcracker” season at San Francisco Ballet—36 performances packed into three weeks—which means that the company is currently serving two distinct audiences.

Continue ReadingLast week I caught up with choreographer Pam Tanowitz and Opera Philadelphia’s current general director and president, countertenor Anthony Roth Costanzo to talk about “The Seasons,” the company’s latest production premiering at the Kimmel Center’s 600-plus seat Perelman Theater on December 19.

Continue ReadingIf Notre-Dame remains one of the enduring symbols of Paris, standing at the city’s heart in all its beauty, much of the credit belongs to Victor Hugo.

Continue ReadingWhen dancer and choreographer Marla Phelan was a kid, she wanted to be an astronaut. “I always loved science and astronomy,” Phelan said.

Continue Reading

comments