Talent Time

It’s “Nutcracker” season at San Francisco Ballet—36 performances packed into three weeks—which means that the company is currently serving two distinct audiences.

Continue Reading

World-class review of ballet and dance.

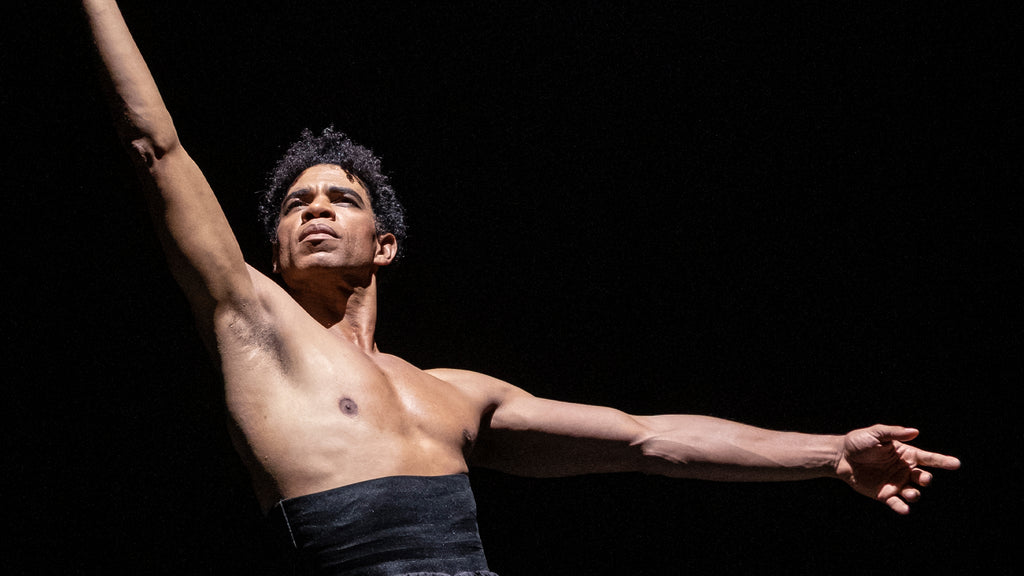

It is a cruel dichotomy that ballet, at its finest, demands a young body and an old soul. The legendary Cuban dancer Carlos Acosta trained relentlessly to come out of retirement last year for a performance of classical works in celebration of his 50th birthday at the Royal Ballet, where he spent most of his professional career. But even he would tell you his still admirably chiseled body is more suited to a contemporary repertoire these days.

Performance

Place

Words

It’s “Nutcracker” season at San Francisco Ballet—36 performances packed into three weeks—which means that the company is currently serving two distinct audiences.

Continue ReadingLast week I caught up with choreographer Pam Tanowitz and Opera Philadelphia’s current general director and president, countertenor Anthony Roth Costanzo to talk about “The Seasons,” the company’s latest production premiering at the Kimmel Center’s 600-plus seat Perelman Theater on December 19.

Continue ReadingIf Notre-Dame remains one of the enduring symbols of Paris, standing at the city’s heart in all its beauty, much of the credit belongs to Victor Hugo.

Continue ReadingWhen dancer and choreographer Marla Phelan was a kid, she wanted to be an astronaut. “I always loved science and astronomy,” Phelan said.

Continue Reading

This performance was transfixing throughout and left me utterly transported and awed. My friend and I sat in silence at the end, barely able to breathe “Wow.” The piece is deeply moving as well as gorgeous. Please tell me it was recorded so I can see it again!

Carrie, so glad to that. you are writing for Fjord. I was mesmerized by Carlos Acosta’s performance as well as his partner’s. They brilliantly performed choreography that was fluid yet very difficult. It’s wonderful that his friendship with Ariel has endured for so many years since they were children in Cuba. I hope he returns to America soon.