What influence did Nino Rota’s music have on the choreography? You're using a mix of his film scores in your production.

I listened to the suite that he composed for the 1966 ballet [choreographed by Mario Pistoni for La Scala], and thought, “I need more music. Perhaps we can use several of his compositions.” I asked Natália if she could work with this idea. She listened to a lot of Rota’s music to see if different pieces could work together dramatically. Music for film is very powerful and has many layers. It has made it easier to move from one point to another in the ballet, from the mundane to the spiritual. The music and Natália’s compilation really enables these transitions.

How did you approach putting your design team together? What it an early decision to work with the former dancer now set designer Otto Bubeniček, who grew up in a circus family?

We didn't know Otto had grown up around the circus actually. I first met Otto as a dancer at Hamburg Ballet. It was Johan who introduced me to his design work. They had both been involved in Yuka Oishi’s “Rasputin” [with set design by Bubeniček] and Johan loved working with him. Otto’s sets are very adaptable and cleverly done. We asked him whether he would consider creating something for “La Strada,” something compact and uncomplicated because we want to tour the ballet. It’s been wonderful to work with him on our set and also the costumes. I think Otto has been excited to bring all the images and colours, and details he knows about circus life to the design. We’ve also been working with lighting designer Andrea Giretti from La Scala, who Natalia has collaborated with before and felt had the right sensitivity for this ballet.

Have you enjoyed the role of producer in making “La Strada?”

It’s been an intriguing journey for me, learning how to build a team that works well together. You make mistakes, of course, but if you can be open to change, when it's needed, or acknowledge an issue and say, “OK. How do we move forward? Do we need more help?”, it’s a fascinating process.

You've spoken in the past about your love of telling stories through classical ballet. How can we bring these stories alive today and make them relevant for contemporary audiences?

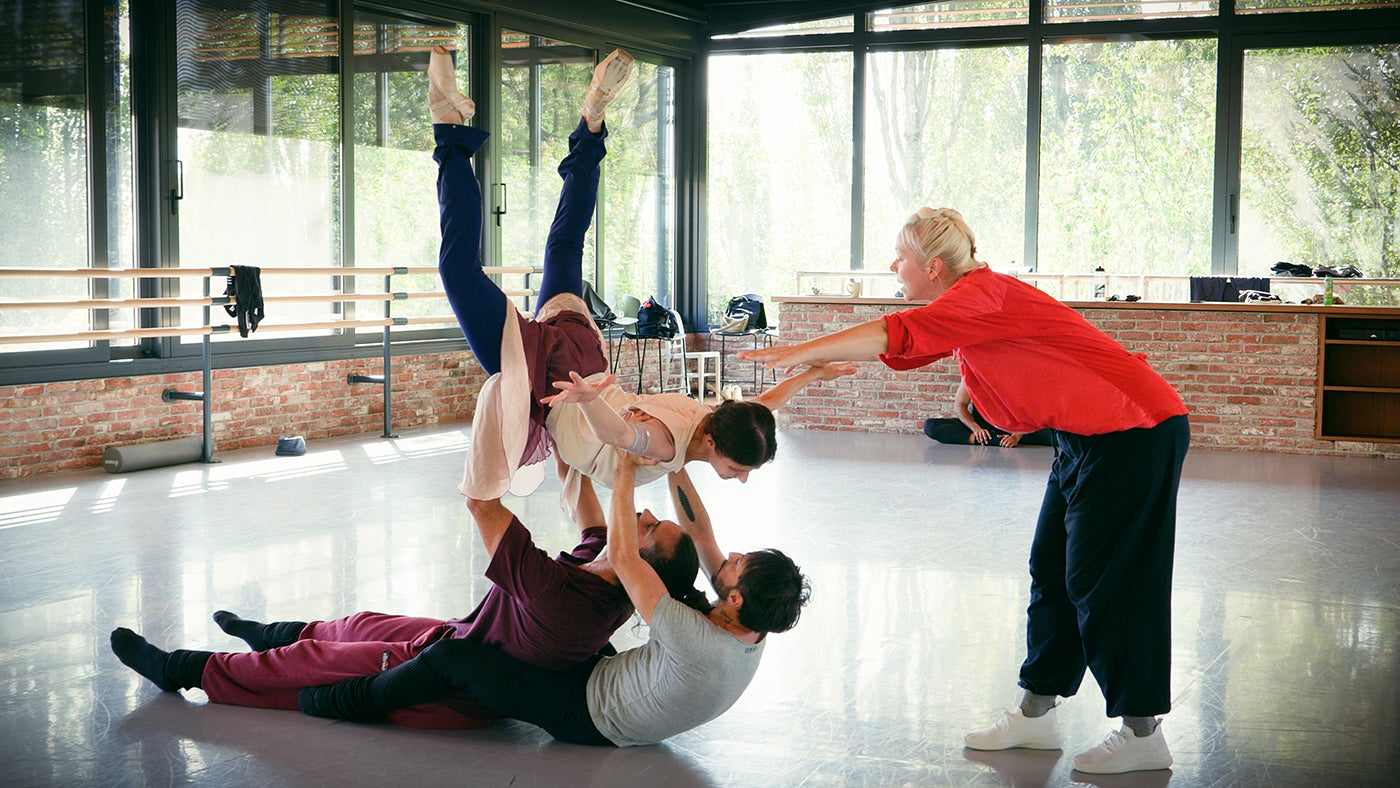

A few things need to happen. The person at the front of the studio has to know how to do this, and have the desire to do it. And the dancers have to be open enough to explore something new. Communication in dance comes from saying something, listening and then answering. Now, in my opinion, it’s often become too much about just saying and answering, saying and answering. The listening part has disappeared. When someone offers their hand in a dance, how do you respond to that hand? With passion? With hesitation? With excitement? With presence—“I’m here too.” I feel the nuance is often lost at the moment. A ballet may look stunning and the audience may enjoy the aesthetics, but you might not necessarily move or connect with a 17-year-old who's watching it. They may have seen someone turning on their head [in street dance], so someone balancing on pointe is not that special.

I remember dancing "Don Quixote,” sometimes and we all laugh at ‘Papa’ [Don Lorenzo, Kitri’s father], because he's so silly. But he's a single father raising his daughter. That’s someone’s real life today. Before I get married [dancing the role of Kitri], I can say, “Papa, thank you. I'm sorry I gave you a hard time, but look, I turned out well. Thank you for this.” These moments are often missing today, I feel. You can dance a ballet, but are you living or telling the story from a more human perspective? “Don Q” is the least dramatic story ballet, but the one I’ve found hardest to dance because of those reasons.

comments