The Two of Us

When I think of the desert, the first impression that comes to mind if of unrelenting heat, stark shadows, the solitude of vast space, occasional winds, and slowness.

Continue Reading

World-class review of ballet and dance.

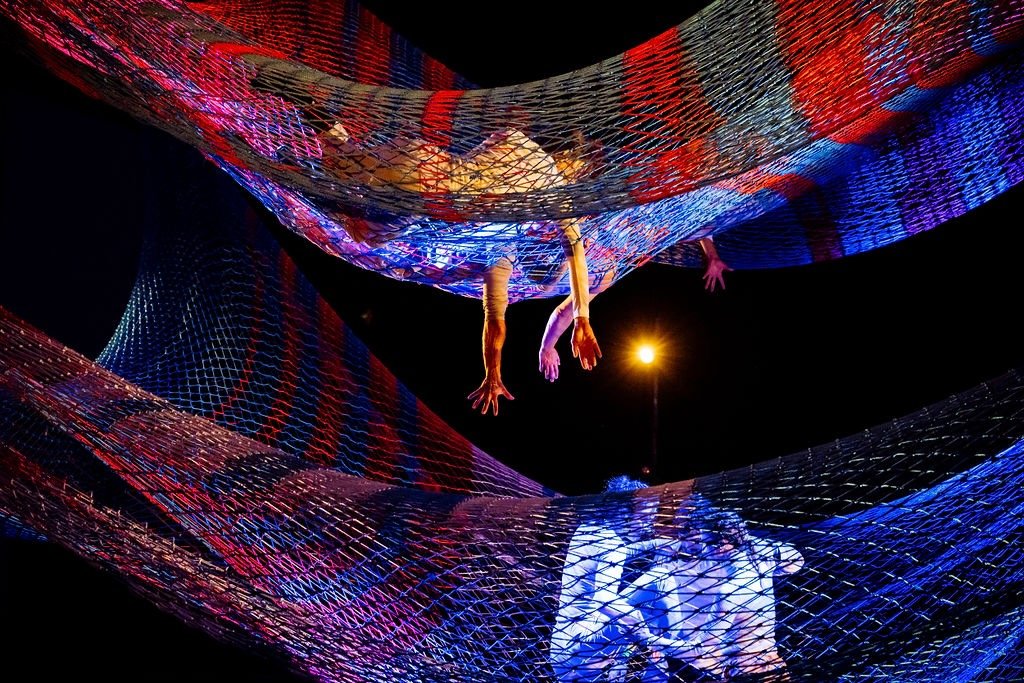

On one of the longest days of sunlight, the innovative, multi-disciplinary performance outpost in New York’s Hudson Valley, PS21, is presenting a “sneak preview” of a work under development in an onsite, four-week residency. The venue, with its 100 acres of unspoiled landscape, is dedicated to hosting residencies for the incubation of adventurous and oftentimes unclassifiable work. Surrounded by green slopes and leaf-laden trees, the open-air Pavilion Theater has been transformed with a black Marley floor in place of the usual seating area. Occupying the vertical space overhead, are two giant net sculptures by Janet Echelman. Suspended one above the other, they stretch across almost the entire length of the performance area. The audience is seated around this great centerpiece for a special preview of Rebecca Lazier’s “Noli Timere,” which means in Latin “Be Not Afraid.”

In an interview during the last week of the residency, I spoke with Lazier about the development of the production and the social practice it inspires. This conversation has been condensed and edited for clarity.

“Uncommonly intelligent, substantial coverage.”

Your weekly source for world-class dance reviews, interviews, articles, and more.

Already a paid subscriber? Login

When I think of the desert, the first impression that comes to mind if of unrelenting heat, stark shadows, the solitude of vast space, occasional winds, and slowness.

Continue ReadingTwo works, separated by a turn of the century. One, the final collaboration between Bill T. Jones and Arnie Zane; the other, made 25 years after Zane’s death.

Continue ReadingLast December, two works presented at Réplika Teatro in Madrid (Lucía Marote’s “La carne del mundo” and Clara Pampyn’s “La intérprete”) offered different but resonant meditations on embodiment, through memory and identity.

Continue ReadingIn a world where Tchaikovsky meets Hans Christian Andersen, circus meets dance, ducks transform and hook-up with swans, and of course a different outcome emerges.

Continue Reading

comments