Just Breathe

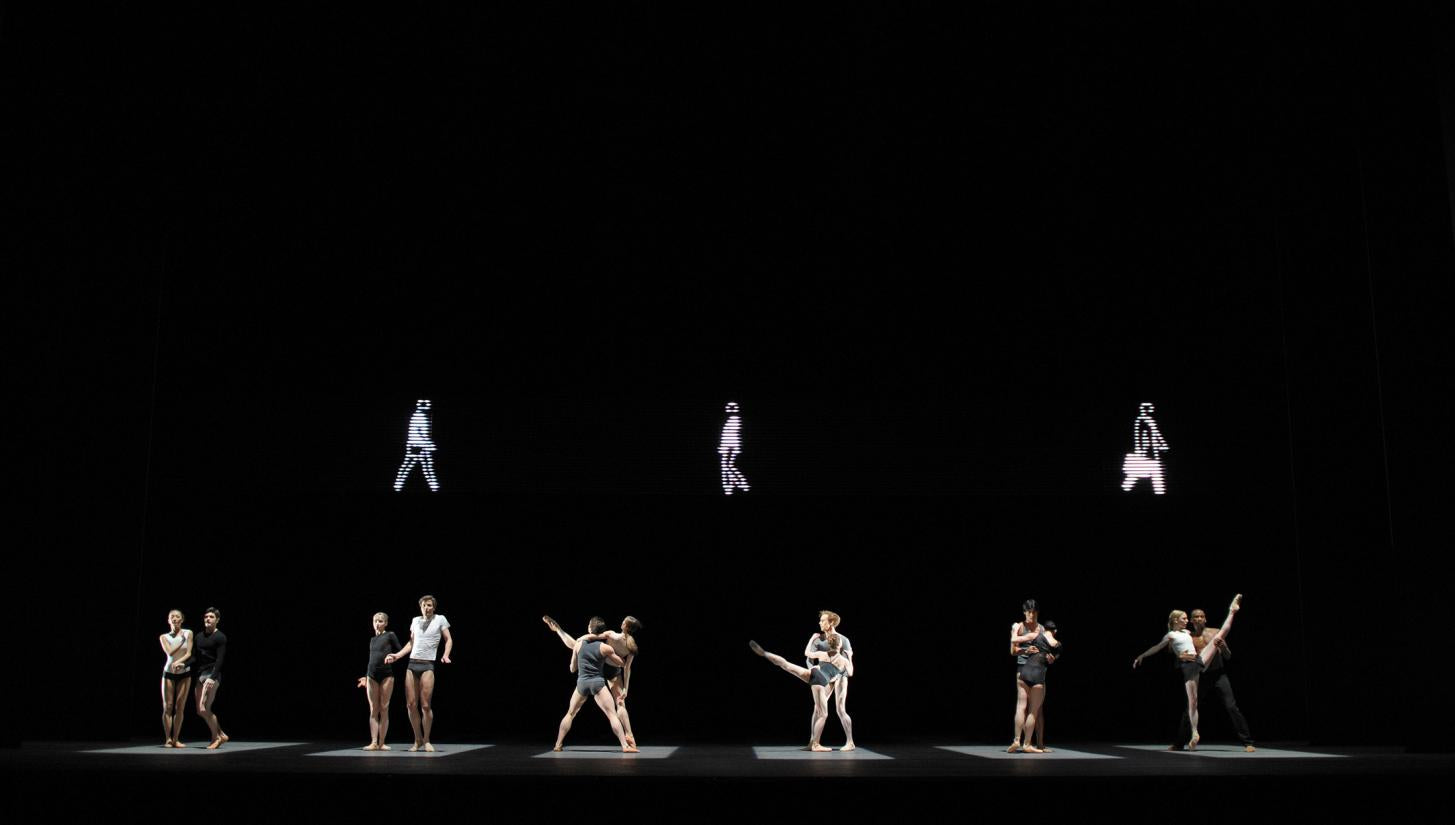

Just over a year ago, I made an early decision to retire from my career as a professional dancer. Leaving behind the glory of the stage, the grind of endless hours in the studio . . . the past 16 years of my life dedicated to performing art. I know for certain that not one day has gone by that I haven’t considered my decision, contemplated my timing . . . wondered what ballet I might be rehearsing or injury I might be nursing if I was still “in the game.” I go to the theater frequently to get my...

Continue Reading