The Two of Us

When I think of the desert, the first impression that comes to mind if of unrelenting heat, stark shadows, the solitude of vast space, occasional winds, and slowness.

Continua a leggere

World-class review of ballet and dance.

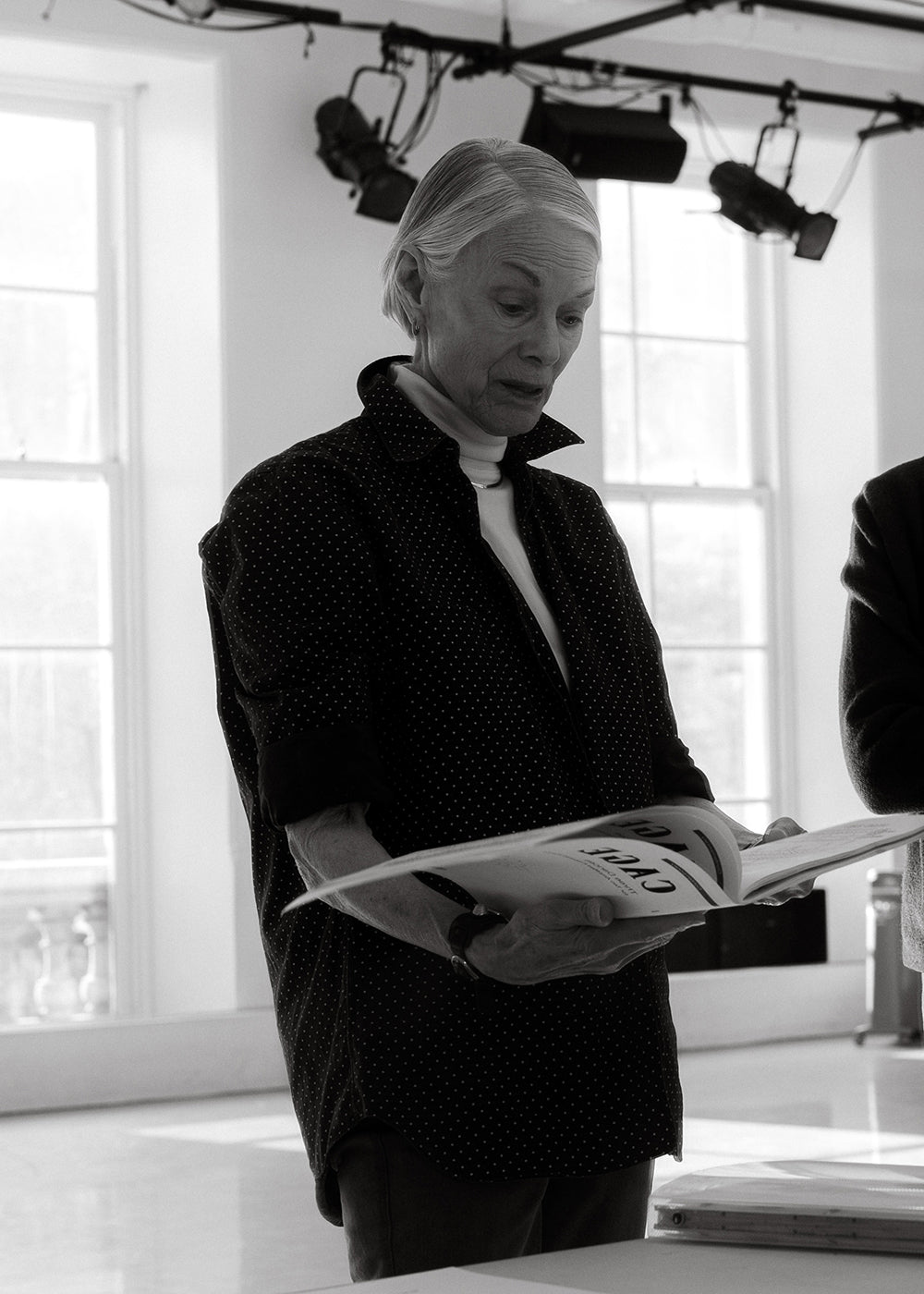

Listening to John Cage’s “Three Dances (for prepared piano)” is a wonderfully contradictory experience. The composer disrupts our auditory expectations by placing an assortment of small objects such as erasers, screws, and bolts, among the piano strings. A musician plays the piano in the typical manner, but instead of a harmonic tone, we hear more percussive sounds of kettle drums, timpani, xylophone, tin cans, even bells. One can imagine how an artist like Lucinda Childs, who was part of the Judson Dance Theater radicals in the ‘60s, might be attracted to such a composition. The choreographer is perhaps best known for her distinctive work in Robert Wilson and Philip Glass’s opera “Einstein on the Beach,” and for “Dance,” based on the geometric grid patterns of artist Sol Le Witt. For her newest work, set to Cage’s prepared piano composition, Childs has chosen to showcase the Gibney Dance Company in New York. The piece will premiere as part of Gibney’s season at the Joyce, May 6–11.

“Uncommonly intelligent, substantial coverage.”

Your weekly source for world-class dance reviews, interviews, articles, and more.

Already a paid subscriber? Login

When I think of the desert, the first impression that comes to mind if of unrelenting heat, stark shadows, the solitude of vast space, occasional winds, and slowness.

Continua a leggereTwo works, separated by a turn of the century. One, the final collaboration between Bill T. Jones and Arnie Zane; the other, made 25 years after Zane’s death.

Continua a leggereLast December, two works presented at Réplika Teatro in Madrid (Lucía Marote’s “La carne del mundo” and Clara Pampyn’s “La intérprete”) offered different but resonant meditations on embodiment, through memory and identity.

Continua a leggereIn a world where Tchaikovsky meets Hans Christian Andersen, circus meets dance, ducks transform and hook-up with swans, and of course a different outcome emerges.

Continua a leggere

comments