Moving Stories

The first moments of Risa show the petite Risa Steinberg seated at a sleek desktop in her New York apartment.

Continue Reading

World-class review of ballet and dance.

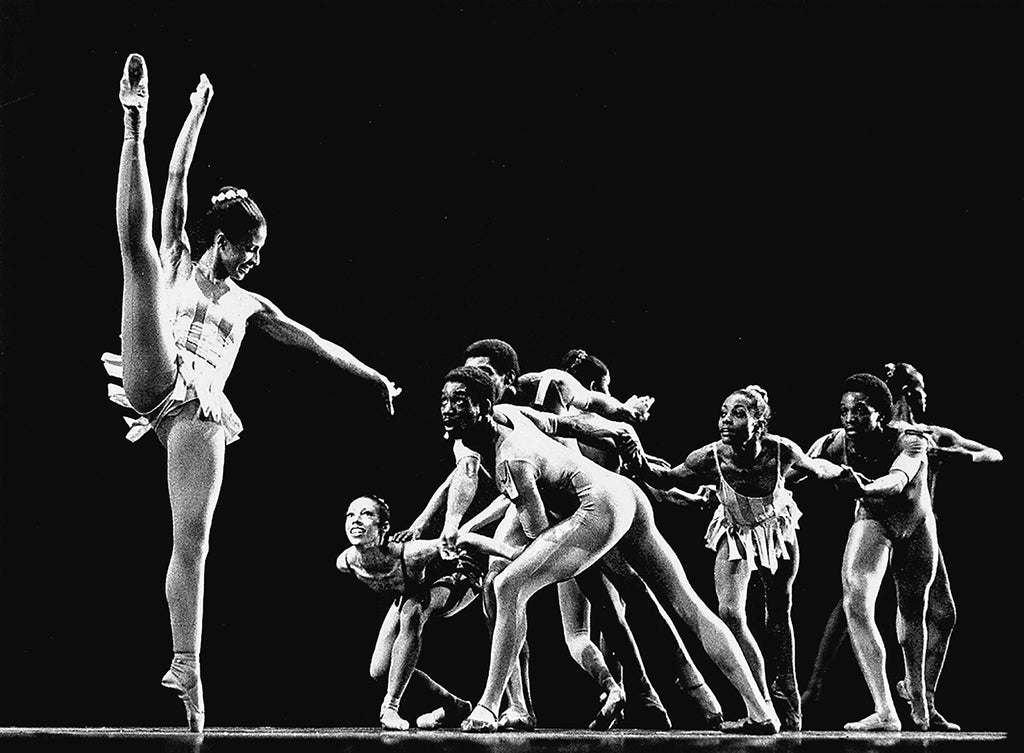

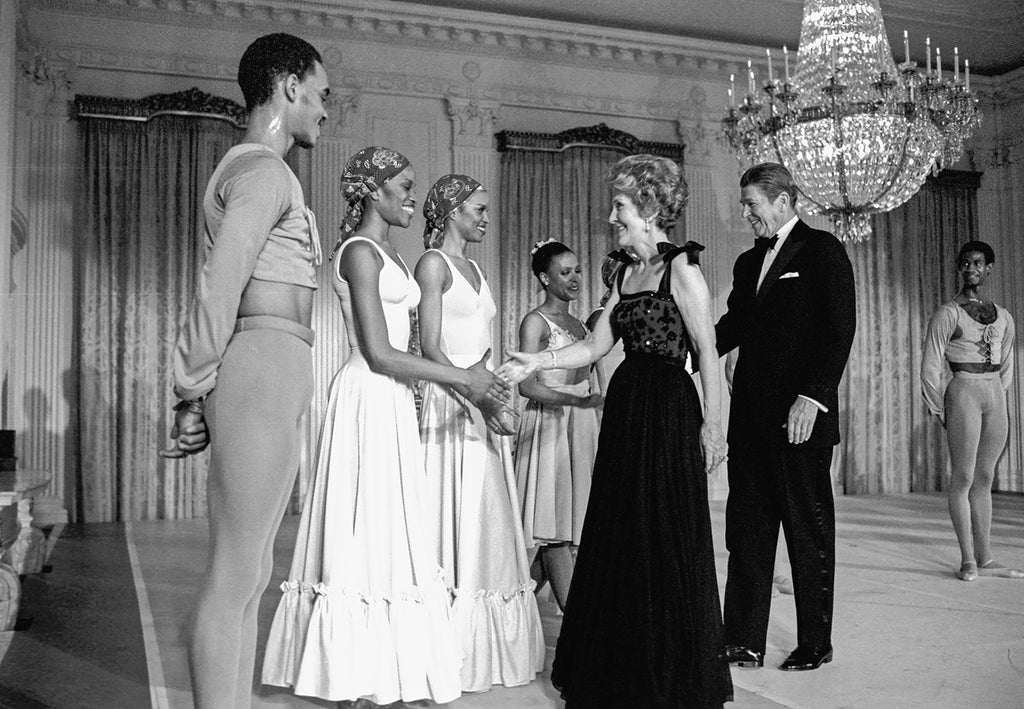

In her new biography, The Swans of Harlem, journalist Karen Valby is witness to the testimony of five pioneering Black ballerinas intimate with the founding history of Dance Theatre of Harlem. She shares their stories from childhood dreams to international stages to obscurity within the larger dance world with a palpable urgency. The mission seems to be somewhat contradictory: on one hand, to give these icons their due before it is too late and, on the other, to restore them to their rightful place in dance history. At intervals she reprises the realization of one of these ballerinas, Sheila Rohan, that she didn’t need to be the star ballerina—“It was enough that I was there. I was there. I was there.”

The first moments of Risa show the petite Risa Steinberg seated at a sleek desktop in her New York apartment.

Continue ReadingThe ballet community in Los Angeles, quite large and scattered, is fond of opining that they live in a “tough town for ballet.”

Continue ReadingDance artists and scholars have long asked the same question: how do we document an art form that, by nature, exists in one moment and is gone the next?

Continue ReadingIn a week of humanitarian crisis, of bodies mobilised and menaced, what a privilege it’s been to take refuge in art that radiates integrity, conviction and splendour.

Continue Reading

Thank you for this detailed, thoughtful, and thought provoking review of a complex and groundbreaking chapter of ballet history. I learned a lot. It makes me want to read The Swans of Harlem to learn much more.