Moving Stories

The first moments of Risa show the petite Risa Steinberg seated at a sleek desktop in her New York apartment.

Continue Reading

World-class review of ballet and dance.

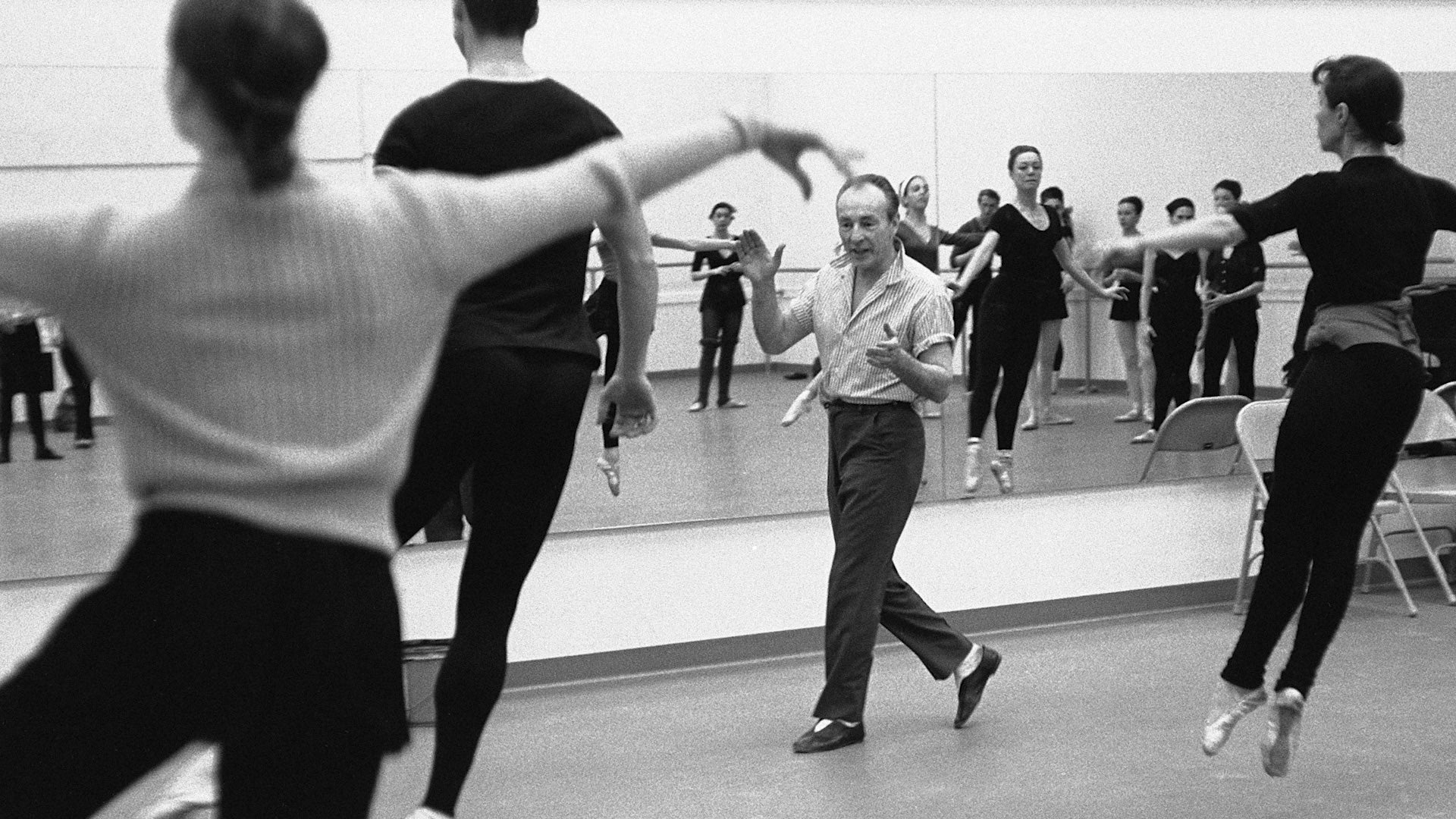

Early this week, the world of New York City Ballet was enlivened by the arrival of more than two hundred dancers, all former members of the troupe. The company is celebrating its 75th year of existence. Some of these dancers, like Robert Barnett, age 98, were there practically at the very beginning. Barnett joined in the company’s second season, in 1949, as did Barbara Bocher Henry, who signed up when she was only fourteen. The two were often partnered onstage in the four years they overlapped at the company. Both traveled to New York for the festivities.

“Uncommonly intelligent, substantial coverage.”

Your weekly source for world-class dance reviews, interviews, articles, and more.

Already a paid subscriber? Login

The first moments of Risa show the petite Risa Steinberg seated at a sleek desktop in her New York apartment.

Continue ReadingThe ballet community in Los Angeles, quite large and scattered, is fond of opining that they live in a “tough town for ballet.”

Continue ReadingDance artists and scholars have long asked the same question: how do we document an art form that, by nature, exists in one moment and is gone the next?

Continue ReadingIn a week of humanitarian crisis, of bodies mobilised and menaced, what a privilege it’s been to take refuge in art that radiates integrity, conviction and splendour.

Continue Reading

Even better!

While Barbara Bocher Henry was clearly a gifted strong technician, when asked to confirm Robert Barnett’s memory of her executing an unassisted arabesque promenade en pointe, she could not take credit. She could however do it unassisted on demi-pointe and once remembers doing 10 pirouettes en pointe at La Scala!