Mishima’s Muse

Japan Society’s Yukio Mishima centennial series culminated with “Mishima’s Muse – Noh Theater,” which was actually three programs of traditional noh works that Japanese author Yukio Mishima adapted into modern plays.

Continue Reading

World-class review of ballet and dance.

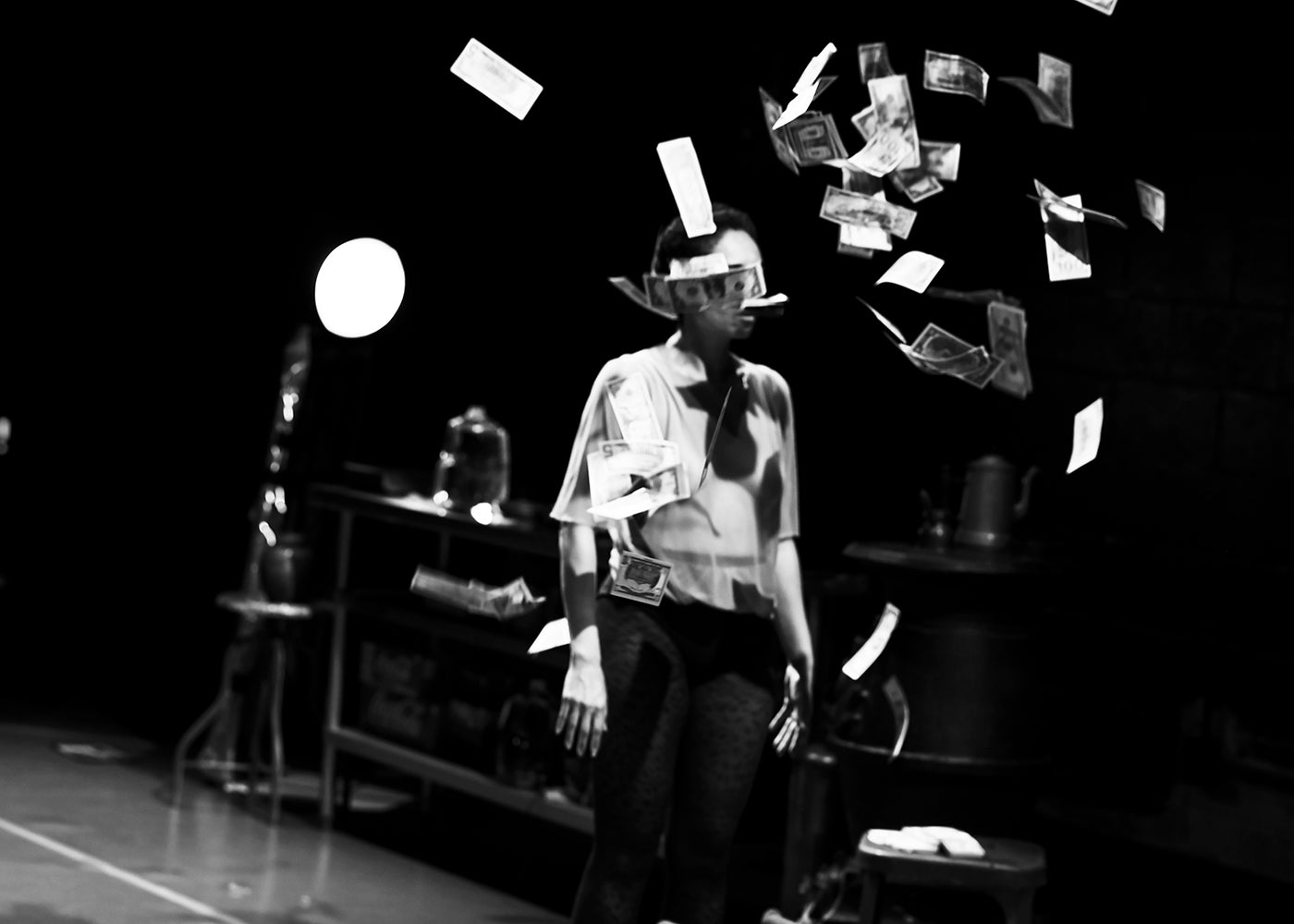

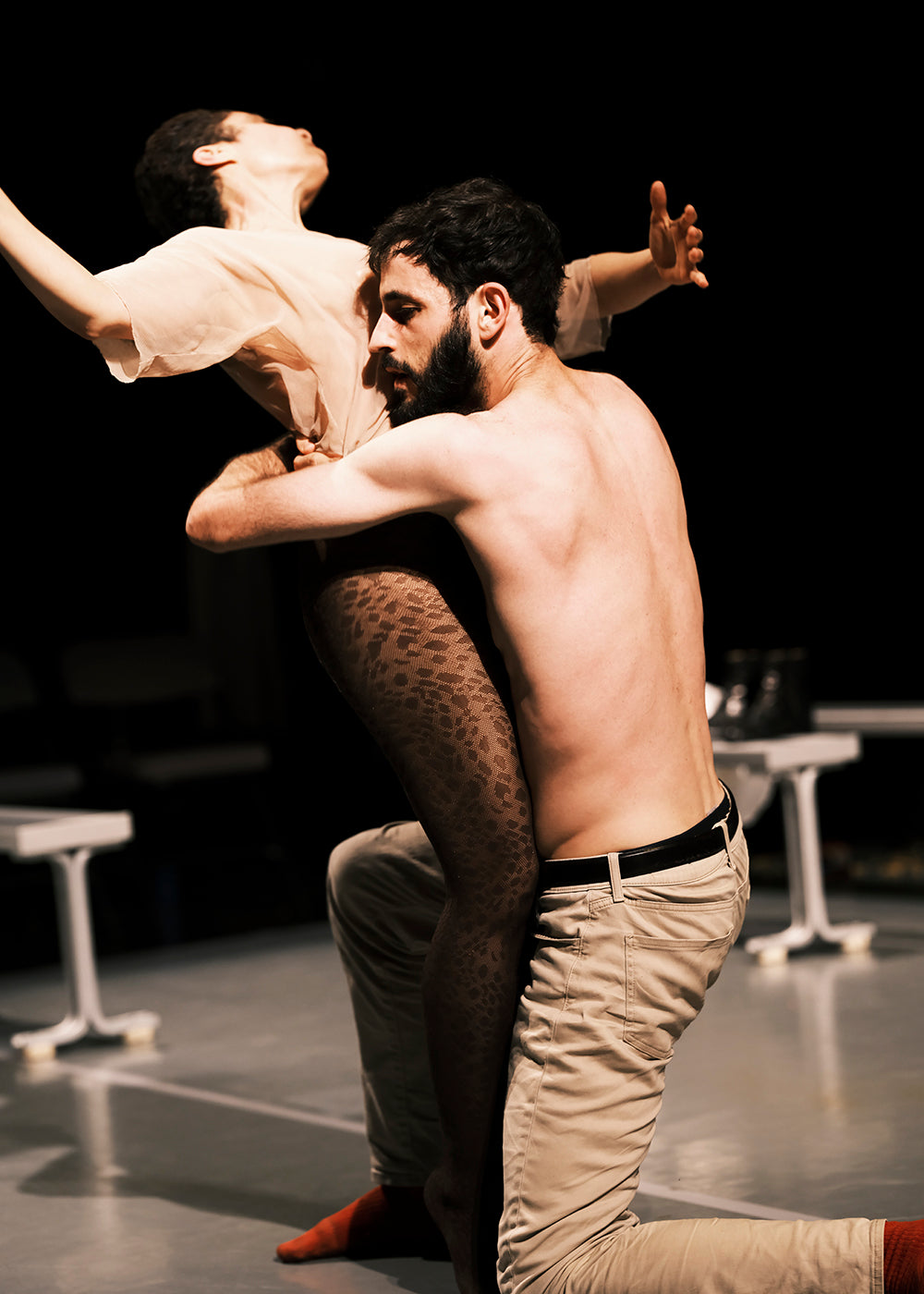

After a decade spent in Los Angeles, Danielle Agami, who founded Ate9 in Seattle in 2012, abruptly decamped for Europe in 2023, leaving somewhat of a gap in the local dance community. To mark her return to the City of Angels, albeit for only a pair of performances, Agami and the latest iteration of her troupe shared a bill with Jacob Jonas the Company at the Kirk Douglas Theatre. Dubbed “Fog,” and presented for two nights over Labor Day weekend, the evenings showcased two world premieres that shared similar idiosyncratic sensibilities—supreme corporeal control akin to a jackhammering of the body, abstract themes and live music—with Jonas’ “Grip,” however, having more cohesion.

Performance

Place

Words

“Uncommonly intelligent, substantial coverage.”

Your weekly source for world-class dance reviews, interviews, articles, and more.

Already a paid subscriber? Login

Japan Society’s Yukio Mishima centennial series culminated with “Mishima’s Muse – Noh Theater,” which was actually three programs of traditional noh works that Japanese author Yukio Mishima adapted into modern plays.

Continue ReadingThroughout the year, our critics attend hundreds of dance performances, whether onsite, outdoors, or on the proscenium stage, around the world.

Continue ReadingOn December 11th, the Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater presented two premieres and two dances that had premiered just a week prior.

Continue ReadingThe “Contrastes” evening is one of the Paris Opéra Ballet’s increasingly frequent ventures into non-classical choreographic territory.

Continue Reading

comments