The Two of Us

When I think of the desert, the first impression that comes to mind if of unrelenting heat, stark shadows, the solitude of vast space, occasional winds, and slowness.

Continue Reading

World-class review of ballet and dance.

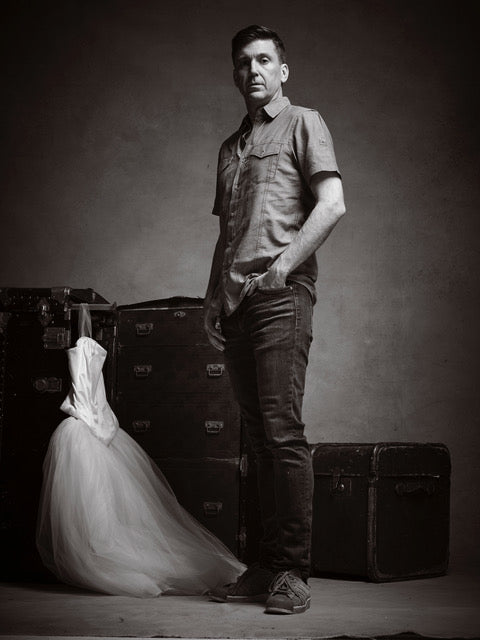

Talk about the marriage of music and dance! Following in the footsteps of George Balanchine, whose works with Igor Stravinsky stretched across decades, Lincoln Jones, artistic director and choreographer of American Contemporary Ballet, continues the tradition when his company dances the world premiere of “The Euterpides.” Performed June 5-28 on a soundstage at the famed Television City in the Fairfax District of Los Angeles, the commissioned ballet was composed by former child prodigy, Alma Deutscher, who turned 20 in February, and who will also conduct a 17-piece ensemble for the first two performances.

“Uncommonly intelligent, substantial coverage.”

Your weekly source for world-class dance reviews, interviews, articles, and more.

Already a paid subscriber? Login

When I think of the desert, the first impression that comes to mind if of unrelenting heat, stark shadows, the solitude of vast space, occasional winds, and slowness.

Continue ReadingTwo works, separated by a turn of the century. One, the final collaboration between Bill T. Jones and Arnie Zane; the other, made 25 years after Zane’s death.

Continue ReadingLast December, two works presented at Réplika Teatro in Madrid (Lucía Marote’s “La carne del mundo” and Clara Pampyn’s “La intérprete”) offered different but resonant meditations on embodiment, through memory and identity.

Continue ReadingIn a world where Tchaikovsky meets Hans Christian Andersen, circus meets dance, ducks transform and hook-up with swans, and of course a different outcome emerges.

Continue Reading

comments