Modern Figures

“Racines”—meaning roots—stands as the counterbalance to “Giselle,” the two ballets opening the Paris Opera Ballet’s season this year.

Continue Reading

World-class review of ballet and dance.

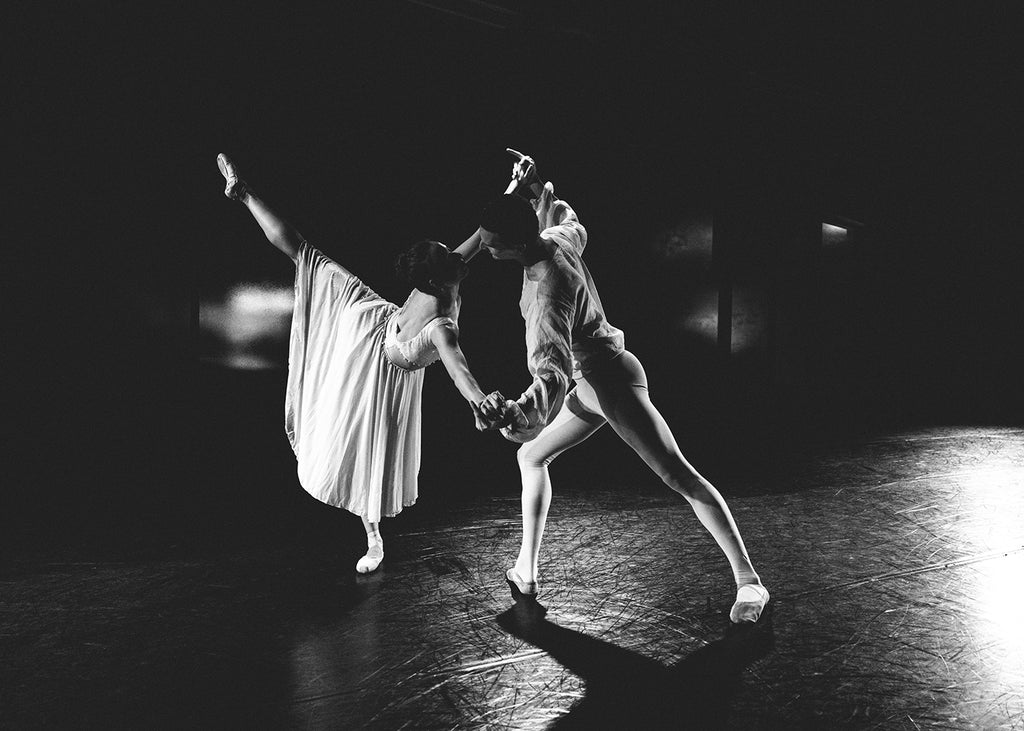

It’s a foregone conclusion that no matter how young, how beautiful, how alive one may be, death can come at any time. And this is what metaphorically transpired on stage at the launch of American Contemporary Ballet’s fourteenth season with a pair of works, “Death and the Maiden,” and “Burlesque IX.” Seen at the troupe’s home—Bank of America Plaza—on opening weekend and running through November 1, the dances, directed and choreographed by ACB founder, Lincoln Jones, once again proved him to be masterful, inventive and courageous in his choices.

Performance

Place

Words

Starting at $49.99/year

Your weekly source for world-class dance reviews, interviews, articles, and more.

Already a paid subscriber? Login

“Racines”—meaning roots—stands as the counterbalance to “Giselle,” the two ballets opening the Paris Opera Ballet’s season this year.

Continue Reading“Giselle” is a ballet cut in two: day and night, the earth of peasants and vine workers set against the pale netherworld of the Wilis, spirits of young women betrayed in love. Between these two realms opens a tragic dramatic fracture—the spectacular and disheartening death of Giselle.

Continue ReadingMichele Wiles’ Park City home is nestled in the back of a wooded neighborhood, hidden from the road by pines and deciduous trees that are currently in the midst of their autumn transformations.

Continue ReadingI joined choreographer and artistic director Cathy Marston over a video call at the end of another day of rehearsals.

Continue Reading

comments