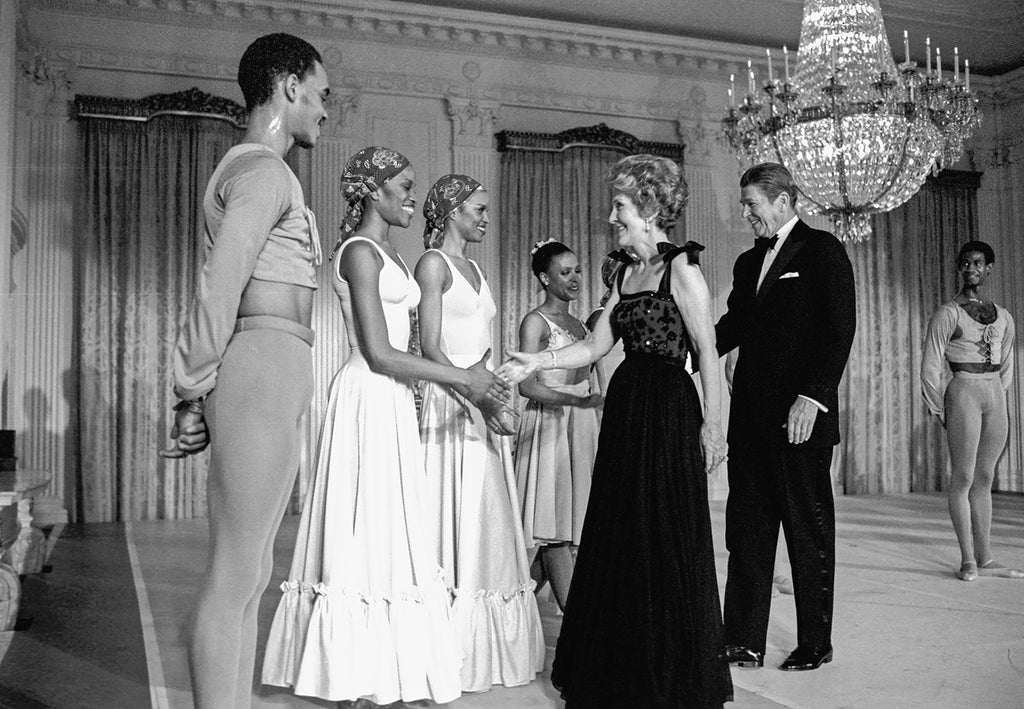

Varby cleverly structures the book like a story ballet, with three acts: a set-up, conflicts, and a resolution that, however, avoids a neat bow. In Act One, Valby narrates the formation of Dance Theatre of Harlem and artfully draws each woman out of her childhood and into its magical fold. Incredibly Rohan, who was already a mother of three living on Staten Island, navigates the ferry, subway, and the immense challenges of childcare to carve out a place for herself in the company. It would be a year before she disclosed to anyone that she was the mother, and not the aunt, of the children she brought in on Saturdays. (Mitchell, who occasionally could be as soft as he was sharp, promptly gave her a raise.) The draw for Rohan, and perhaps all of them, Valby writes, “was the notion of dancing once more in pointe shoes, but this time with her people.”Valby balances the dreamt-of pinnacle of finding oneself in an all-Black classical ballet company with the pressure cooker realities that Mitchell and the company faced, akin to startup culture except with societal mores stacked against you. Monies needed to be raised for performances that began only weeks into the company’s formation.

The author also doesn’t shy away from accounts of Mitchell’s “early prioritization of Caucasian beauty standards,” which took the shape of both colorism and demands that the dancers be bone thin. In one of the weekly Zoom sessions that brought these five dancers back together during the pandemic after many years apart, Sells tells the others, “I think the piece I still haven’t fully come to grips with is that although we were a Black ballet company, we were still always confronted by the imagery of what white women dancers looked like.”

As the company’s first ballet mistress, McKinney-Griffith bore a disproportionate amount of the stress from these tensions. Valby notes her keen diplomacy in her role as Mitchell’s messenger and her advocacy and development of second casts and younger dancers like Shelton-Benjamin and Sells, though ultimately Mitchell’s managerial style would push her away. Sadly, McKinney-Griffith passed away last October, at the age of 74, after a battle with cancer.

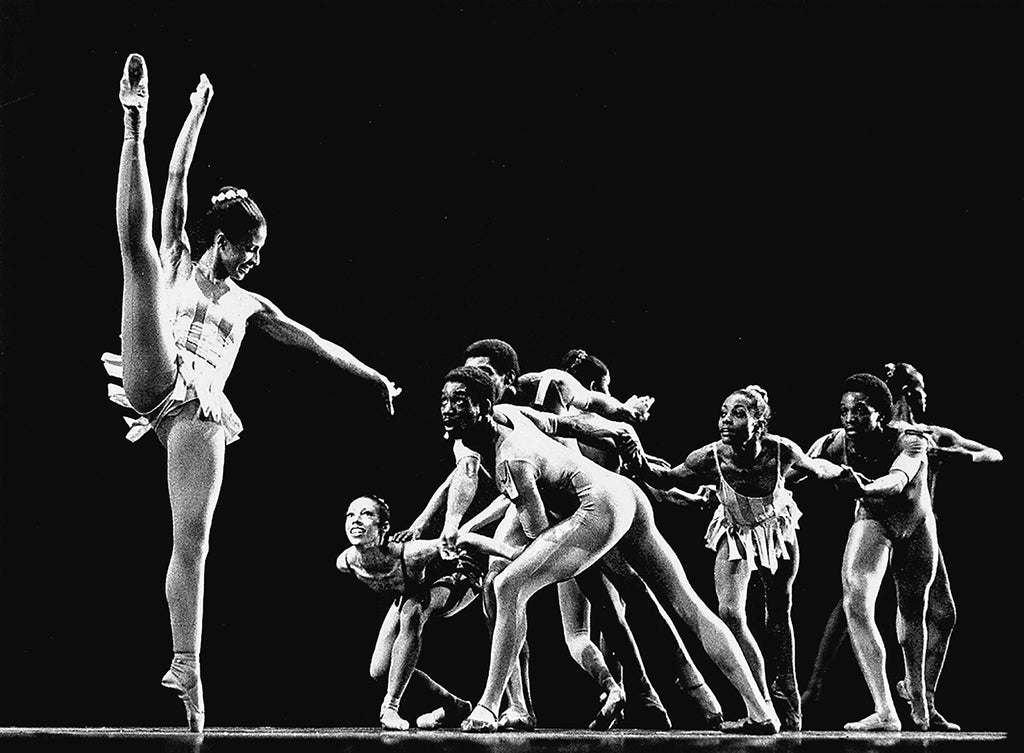

Other founding members, such as Aminah Ahmad (formerly Llanchie Stevenson) and Walter Raines, composer Tania Leon, and choreographer Louis Johnson, also play important supporting roles in the narrative. In one surprising anecdote, Valby relates how DTH came to don tights and shoes that actually matched their skin tone, a policy that majority-white companies are only now adopting. Ahmad was thirty years old and feeling like she might never get Mitchell’s attention for a leading role. She began layering brown tights over pink tights in her warmup, just as she had been dyeing her tutu straps her skin tone, when the realization hit: “Wait, my arms now match my legs! All of a sudden, I’m connected. I’m a whole body instead of half of one.”

comments