Heartfelt Moments

The Australian Ballet’s “Signature Works,” as a whole, is a compact and varied celebration of dance in the moment.

Continua a leggere

World-class review of ballet and dance.

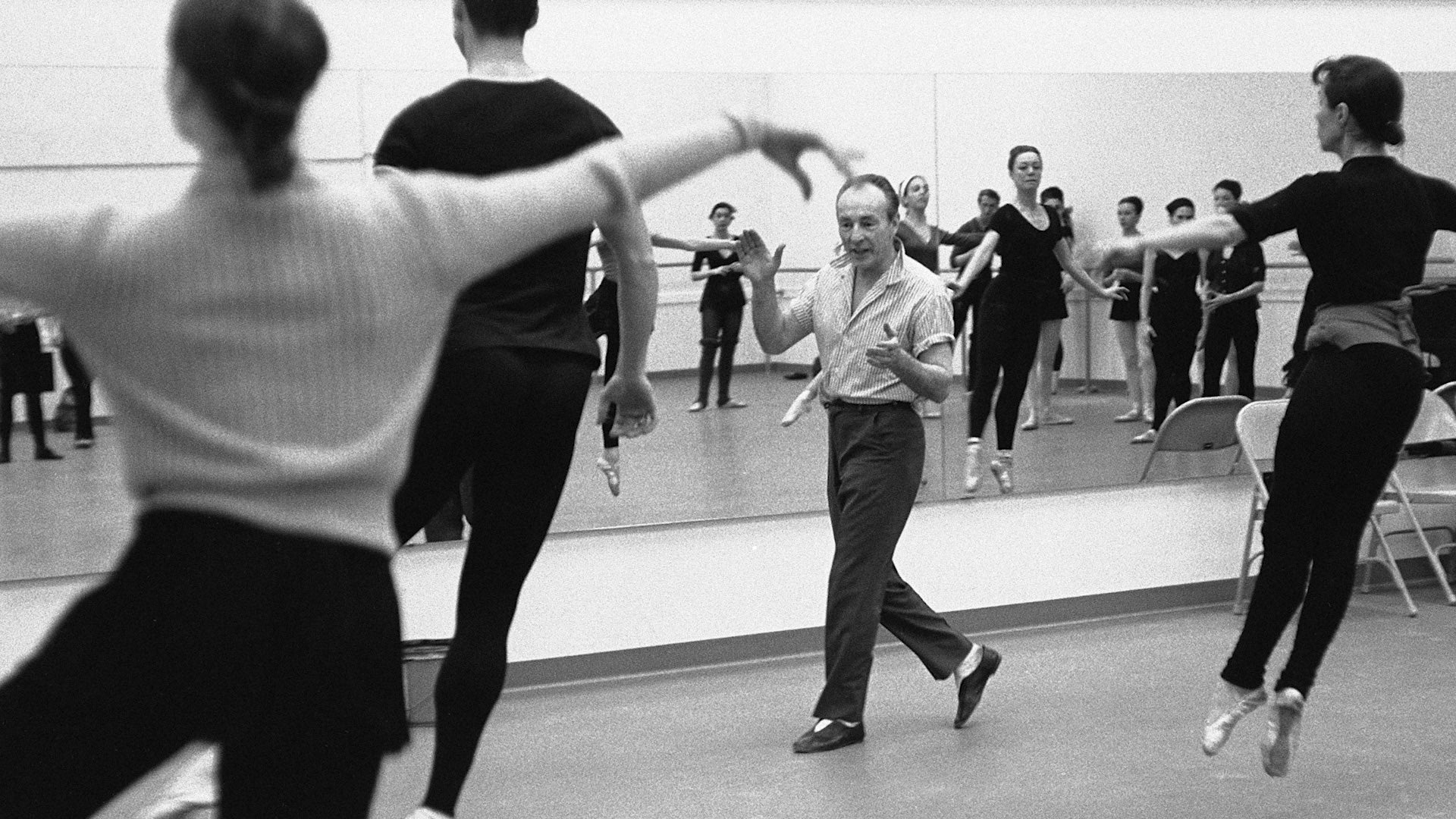

Early this week, the world of New York City Ballet was enlivened by the arrival of more than two hundred dancers, all former members of the troupe. The company is celebrating its 75th year of existence. Some of these dancers, like Robert Barnett, age 98, were there practically at the very beginning. Barnett joined in the company’s second season, in 1949, as did Barbara Bocher Henry, who signed up when she was only fourteen. The two were often partnered onstage in the four years they overlapped at the company. Both traveled to New York for the festivities.

“Uncommonly intelligent, substantial coverage.”

Your weekly source for world-class dance reviews, interviews, articles, and more.

Already a paid subscriber? Login

The Australian Ballet’s “Signature Works,” as a whole, is a compact and varied celebration of dance in the moment.

Continua a leggereThe Joffrey Ballet’s lithe and strong dancers take on four historic works in this mixed-bill “American Icons” programme.

Continua a leggereIn Trisha Brown's 1983 “Set and Reset,” dancers float in and out of the wings like bubbles.

Continua a leggereTalk about perfection! While the countdown is on, as Gustavo Dudamel, music director of the world-class Los Angeles Philharmonic, prepares to exit the stage for the New York Philharmonic (a big boohoo), his presence last weekend at Walt Disney Concert Hall further cemented his status as musical genius, tastemaker and catalyst for good.

Continua a leggere

Even better!

While Barbara Bocher Henry was clearly a gifted strong technician, when asked to confirm Robert Barnett’s memory of her executing an unassisted arabesque promenade en pointe, she could not take credit. She could however do it unassisted on demi-pointe and once remembers doing 10 pirouettes en pointe at La Scala!