The book definitely draws on this theme of friendship, while also exploring how the ballet environment can affect interpersonal relationships more broadly.

The Still Point is about people—that was my main goal. Yes, this is a ballet book, and yes, it's a ballet mom book, but it really is about the journeys of each of these women. There's so many other forces at play. There's grief and loss for all of the characters. Ever, one of the moms, is experiencing the loss of her husband, but Lindsay, another of the moms, has experienced the loss of her marriage. And Josie, a third mom, has been through a series of losses. That's the larger picture that transcends the very specific environment that's been created within ballet.

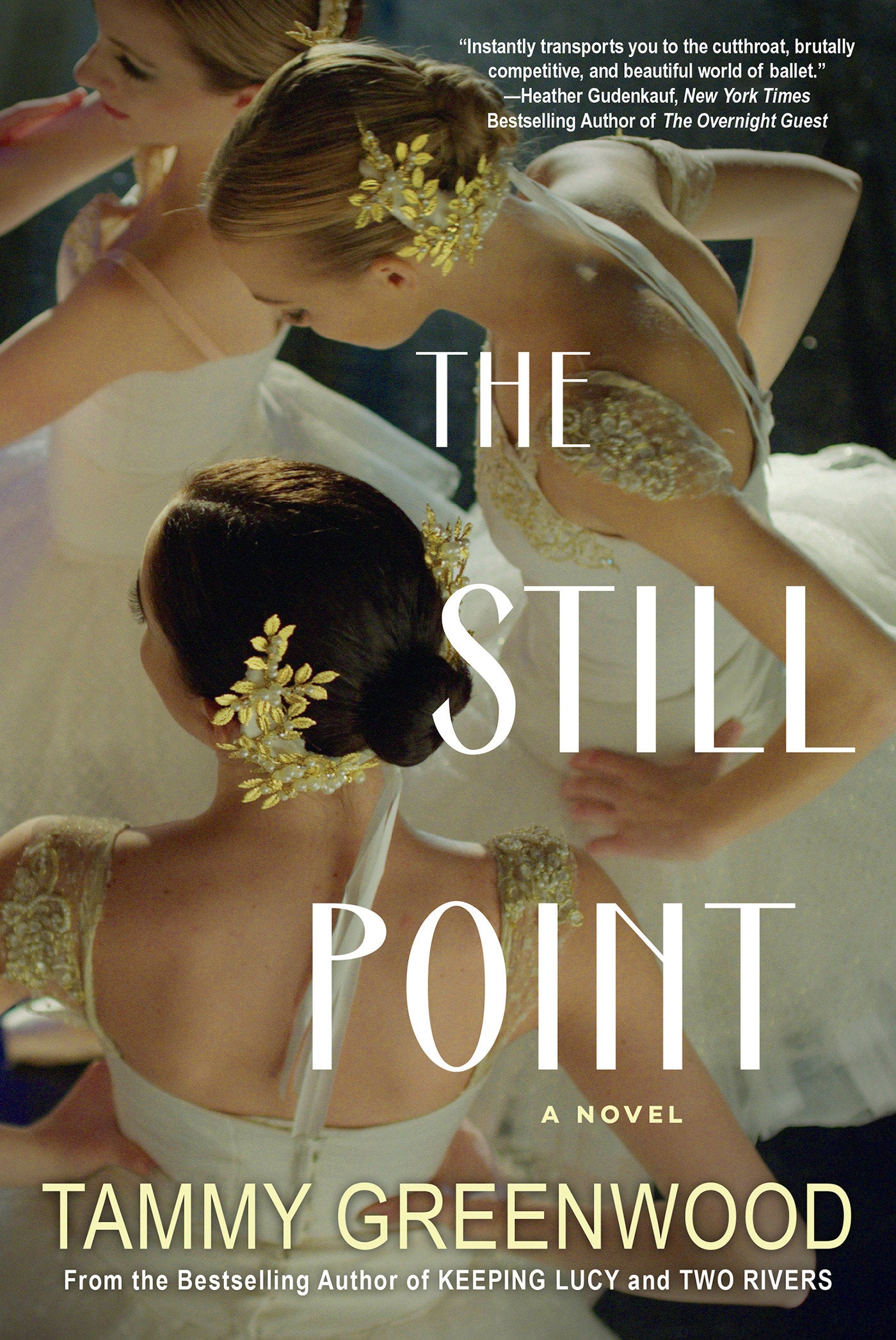

The Still Point doesn’t play into the typical tropes that are often involved in stories about the ballet world, but it remains a page-turner with plenty of drama and spice. How did you find this balance?

I think what happens sometimes with movies and things is, they're created by people who are relying on clichés. They're relying on every dancer having an eating disorder, or these girls putting glass in each other's pointe shoes, which is something I've never seen—it’s just not done. I really wanted to honor the fact that the girls often are very supportive of each other—they're like siblings in a way. The girls that my daughter grew up with were like family. I really wanted to avoid those more tired tropes and go deeper than that. Not to say that girls don't face those struggles, but there's so much more to the training to be a dancer. To have your life, at such a young age, dedicated to making art is amazing. I wanted to really try to be authentic to real dancers’ experiences and the real relationships that develop inside a studio, rather than just going with the cliché. That's the beautiful thing about writing from your own experience: you can offer something that somebody who isn't as familiar with a particular world can’t.

comments