The Two of Us

When I think of the desert, the first impression that comes to mind if of unrelenting heat, stark shadows, the solitude of vast space, occasional winds, and slowness.

Continua a leggere

World-class review of ballet and dance.

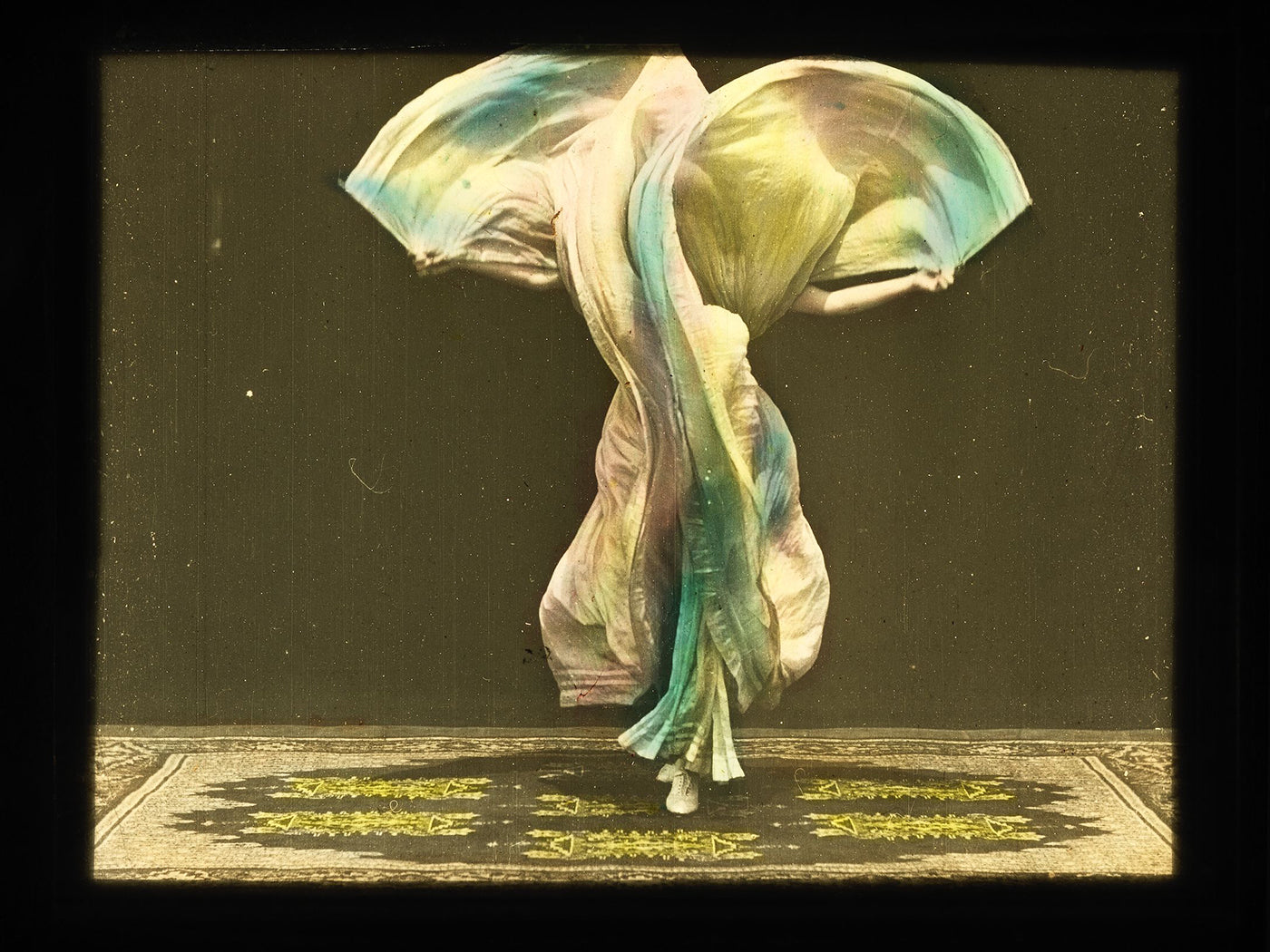

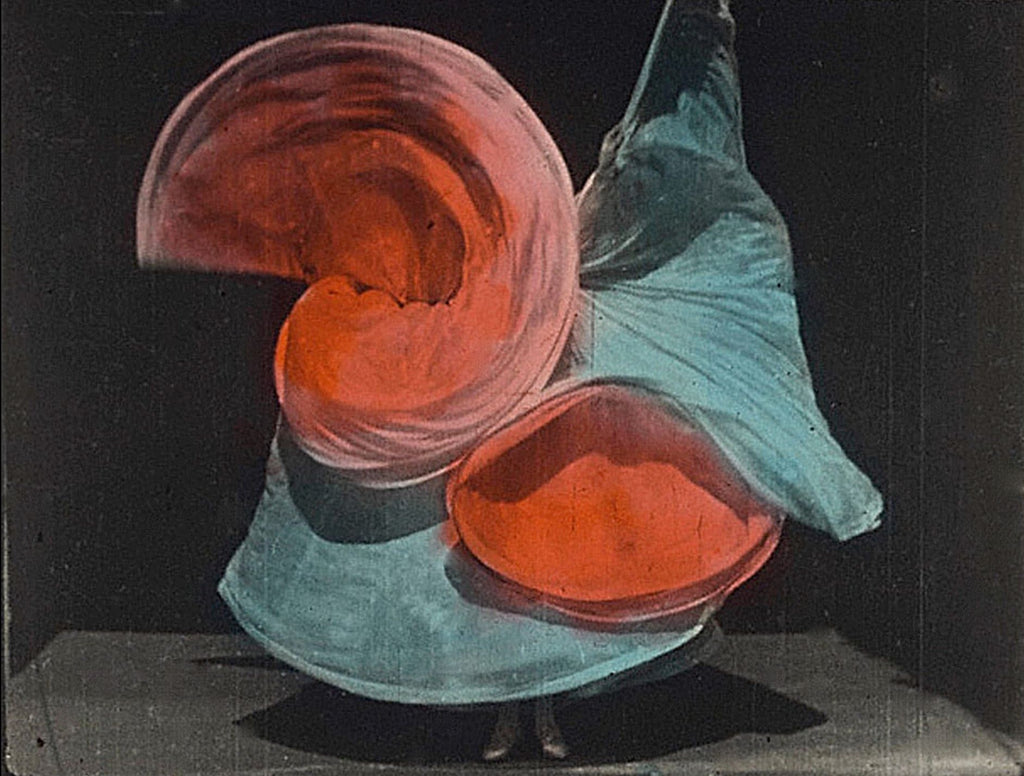

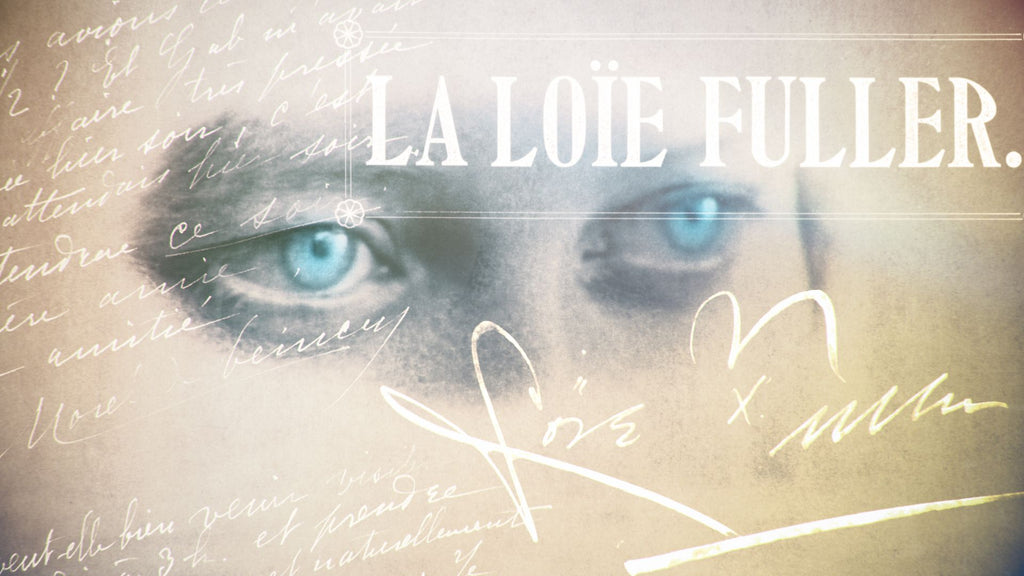

Loïe Fuller, groundbreaking artist, dancer and theatrical maverick, is finally getting her due in the feature-length documentary, Obsessed with Light. Opening at New York’s Quad Cinema on December 6, the film, directed by Zeva Oelbaum and Sabine Krayenbühl, is a meditation on light and the enduring passion to create. Indeed, in pulling back the curtain on Fuller, a sui generis performer who revolutionized the visual culture of the early twentieth century, the duo, best known for their 2016 award-winning film, Letters from Baghdad, has, in essence, directed a film about transformation.

When I think of the desert, the first impression that comes to mind if of unrelenting heat, stark shadows, the solitude of vast space, occasional winds, and slowness.

Continua a leggereTwo works, separated by a turn of the century. One, the final collaboration between Bill T. Jones and Arnie Zane; the other, made 25 years after Zane’s death.

Continua a leggereLast December, two works presented at Réplika Teatro in Madrid (Lucía Marote’s “La carne del mundo” and Clara Pampyn’s “La intérprete”) offered different but resonant meditations on embodiment, through memory and identity.

Continua a leggereIn a world where Tchaikovsky meets Hans Christian Andersen, circus meets dance, ducks transform and hook-up with swans, and of course a different outcome emerges.

Continua a leggere

comments