The Two of Us

When I think of the desert, the first impression that comes to mind if of unrelenting heat, stark shadows, the solitude of vast space, occasional winds, and slowness.

Continua a leggere

World-class review of ballet and dance.

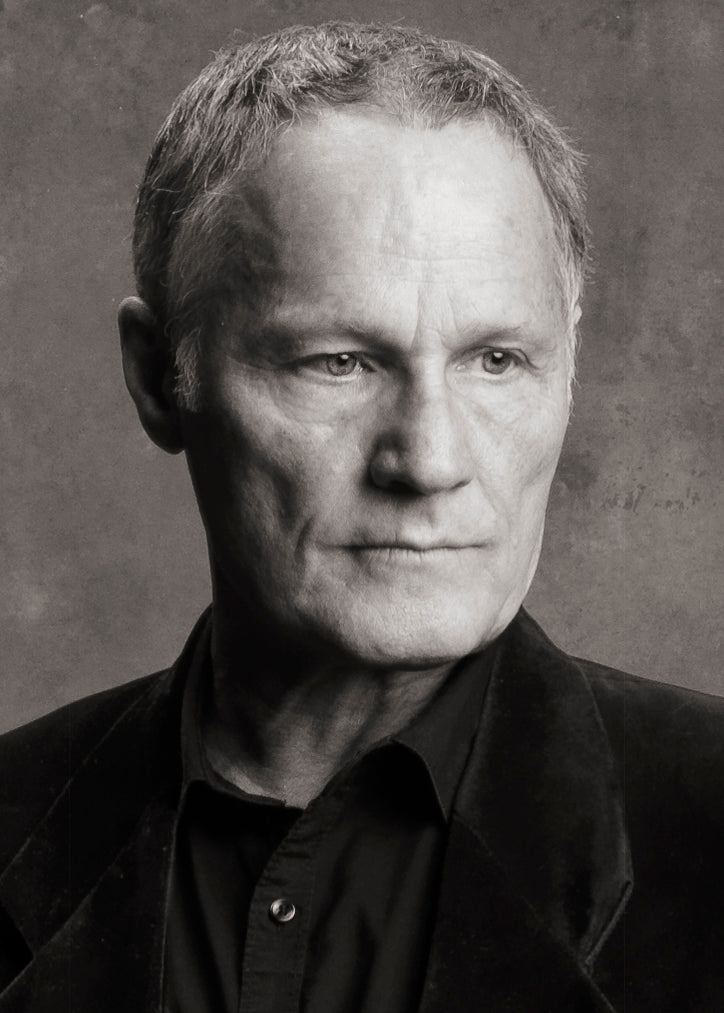

I never set out particularly to be a creator of solos,” says Lar Lubovitch. “But after 60 years in the dance world and 120 dances, I will have made a number of solos.” On Sunday, September 7, Works & Process hosts Lar Lubovitch: Art of the Solo at Guggenheim New York, where the choreographer will show five examples that span his career: the earliest, “Scriabin Dances” made in 1972 for Martine van Hamel of American Ballet Theatre to music of Alexander Scriabin; the most recent, “Desire” made last year for Adrian Danchig-Waring of New York City Ballet as a video project. Danchig-Waring will perform on Sunday, as will Jacquelin Harris, Ashley Green, and Jesse Obremski of Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater, and Craig D. Black Jr. of Hubbard Street Dance Chicago.

“Uncommonly intelligent, substantial coverage.”

Your weekly source for world-class dance reviews, interviews, articles, and more.

Already a paid subscriber? Login

When I think of the desert, the first impression that comes to mind if of unrelenting heat, stark shadows, the solitude of vast space, occasional winds, and slowness.

Continua a leggereTwo works, separated by a turn of the century. One, the final collaboration between Bill T. Jones and Arnie Zane; the other, made 25 years after Zane’s death.

Continua a leggereLast December, two works presented at Réplika Teatro in Madrid (Lucía Marote’s “La carne del mundo” and Clara Pampyn’s “La intérprete”) offered different but resonant meditations on embodiment, through memory and identity.

Continua a leggereIn a world where Tchaikovsky meets Hans Christian Andersen, circus meets dance, ducks transform and hook-up with swans, and of course a different outcome emerges.

Continua a leggere

comments