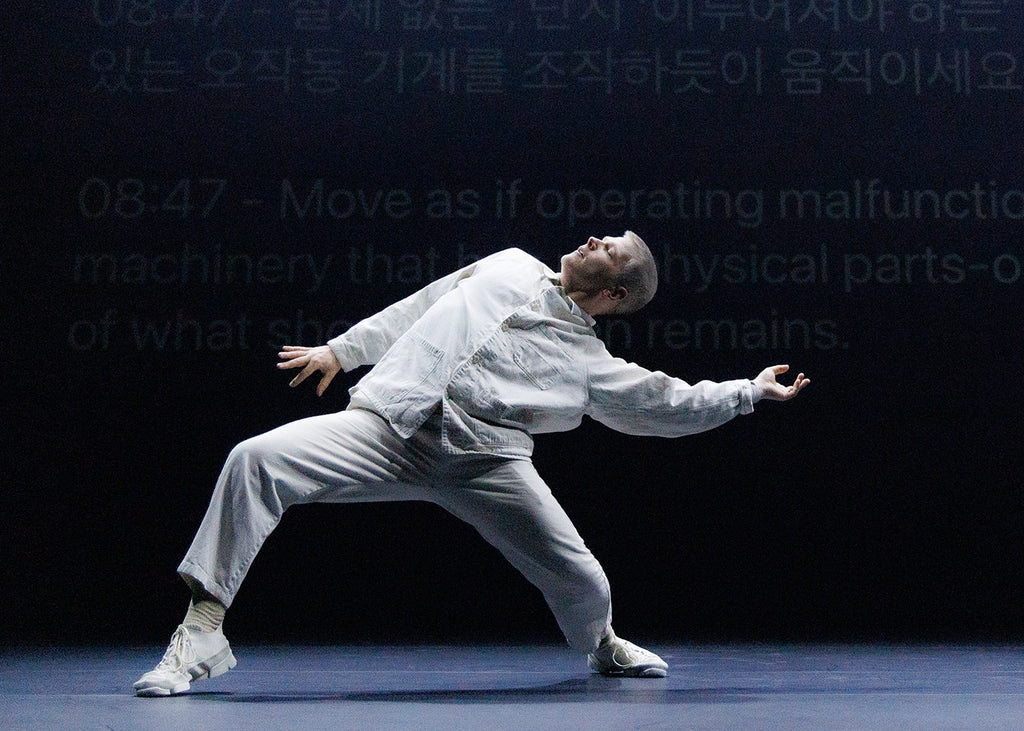

All of which flows, as rivers do, into “A Figure of Speech” by Macindoe. Macindoe, as choreographer, performer, sound designer, coder, and one-man band, stretches out his palms as if upon them tiny sensors rest. He makes movements suggestive of a bodily vessel having consumed a museum didactic. He constantly jolts his torso at a 90-degree angle. He demonstrates what human thought might look like. Moving quickly from one sensation to the next, these movements are, of course, instructions. With the black curtains now parted, projected on the wall, they are a series of timed, poetic prompts, written in both English and Korean. Reminiscent of his earlier work, “Plagiary”, a “dance performance experiment that employed Artificial Intelligence as a speaking choreographer and playwright,”[3] presented as part of Melbourne’s Now or Never, and Sydney’s Unwrapped festivals in 2024, Macindoe lifts his rib cage as high as he can, as if something is pushing from underneath. He proceeds to feel his way through a greenhouse, as if constantly hitting obstructions, his face wincing as a knee appears to clip the edge of a potting table. Comprised of several parts, all of which move quickly, I have to make a choice to read the words or the body or swing between the two; there is no pause. This perhaps is what it means to be human. I fail to scan it all, but I can compose what I assemble in my mind’s eye in a way to derive meaning that relates to me. Computer language[4] places the emphasis on a familiar, unfamiliar spot, and renders me off-kilter.

comments