Feminine Mystique

Dresses, domestic chores, grief. A community of women more feral than feminine. Five performers wear a changing selection of 40 dresses that serve as both costume and prop.

Continua a leggere

World-class review of ballet and dance.

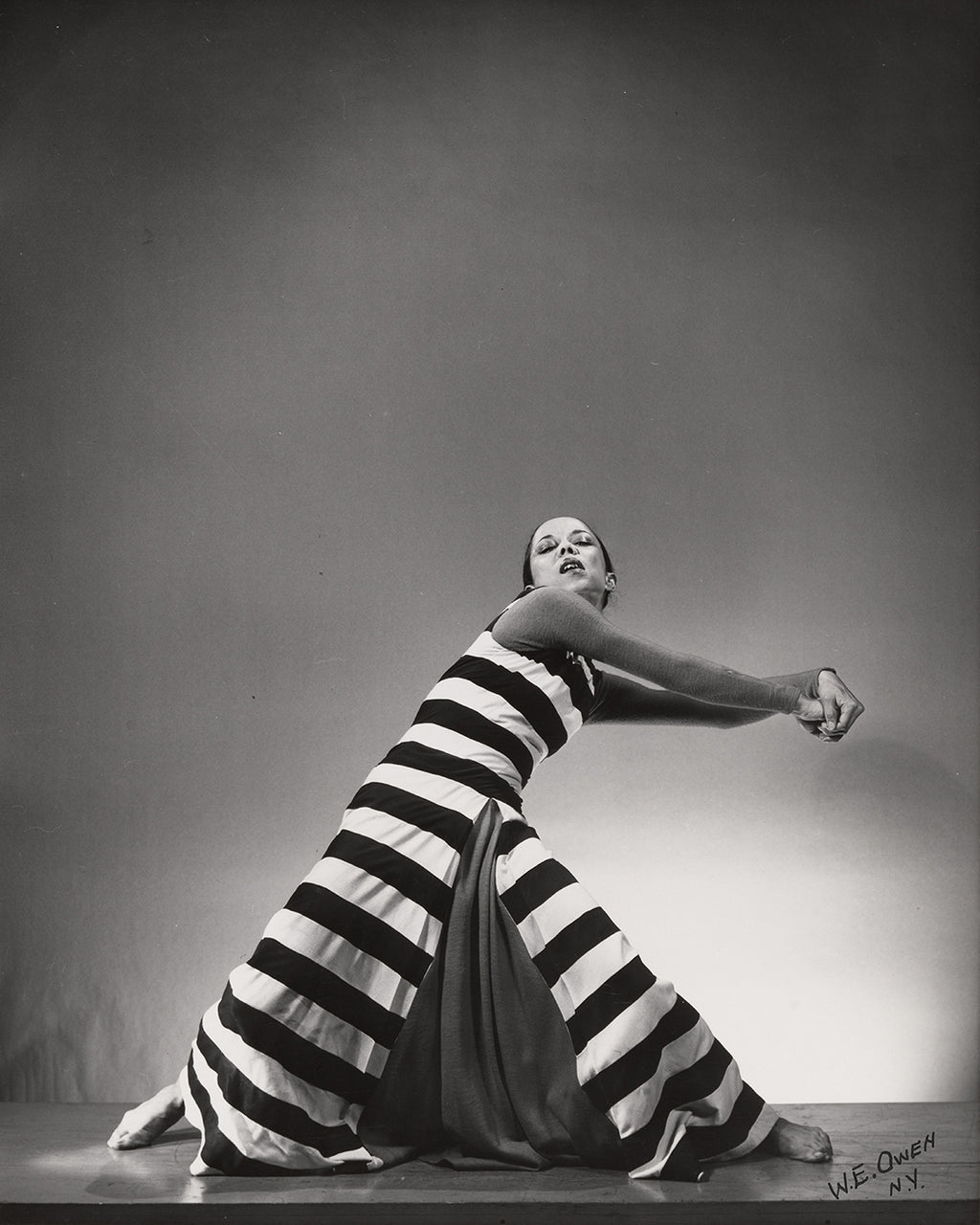

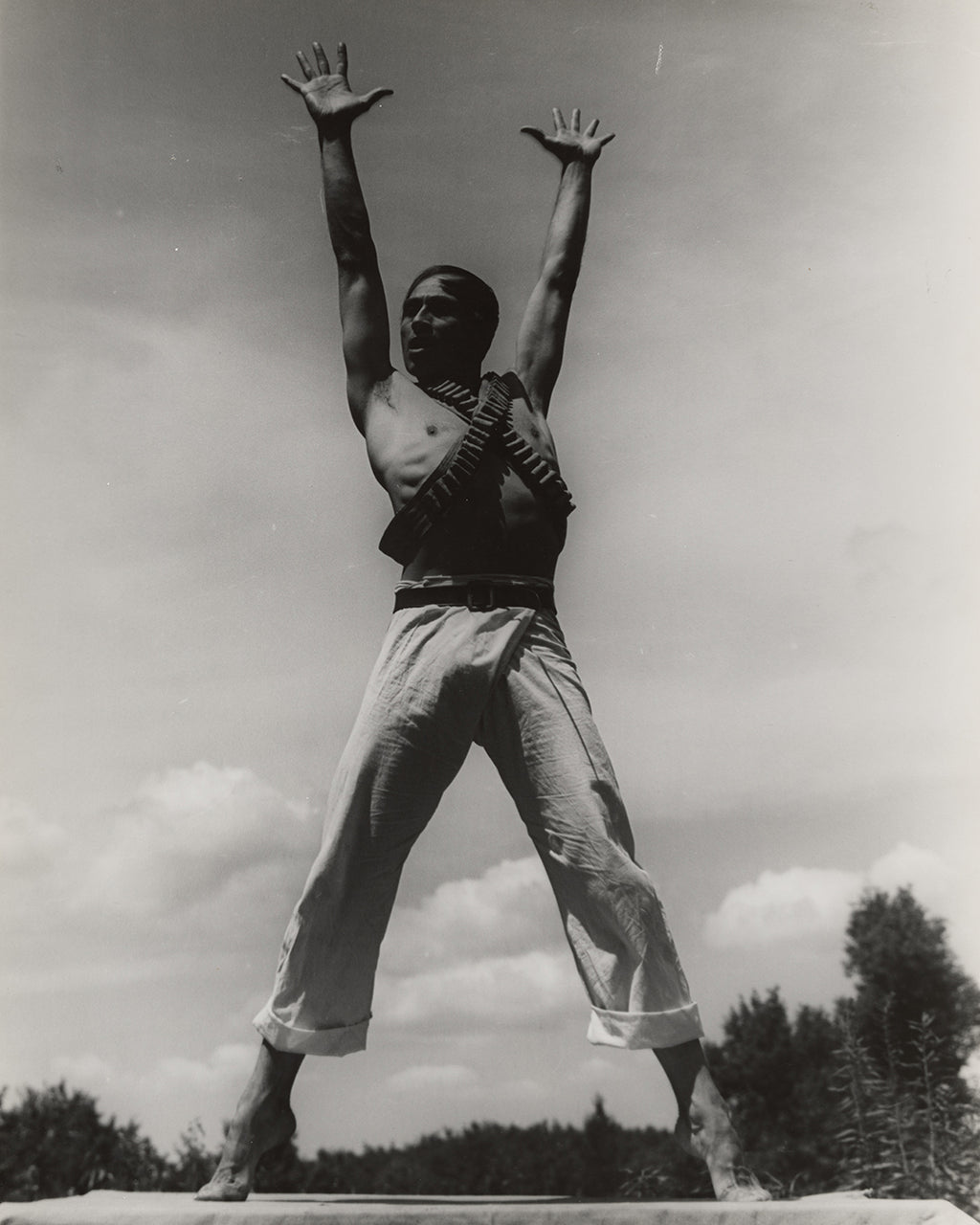

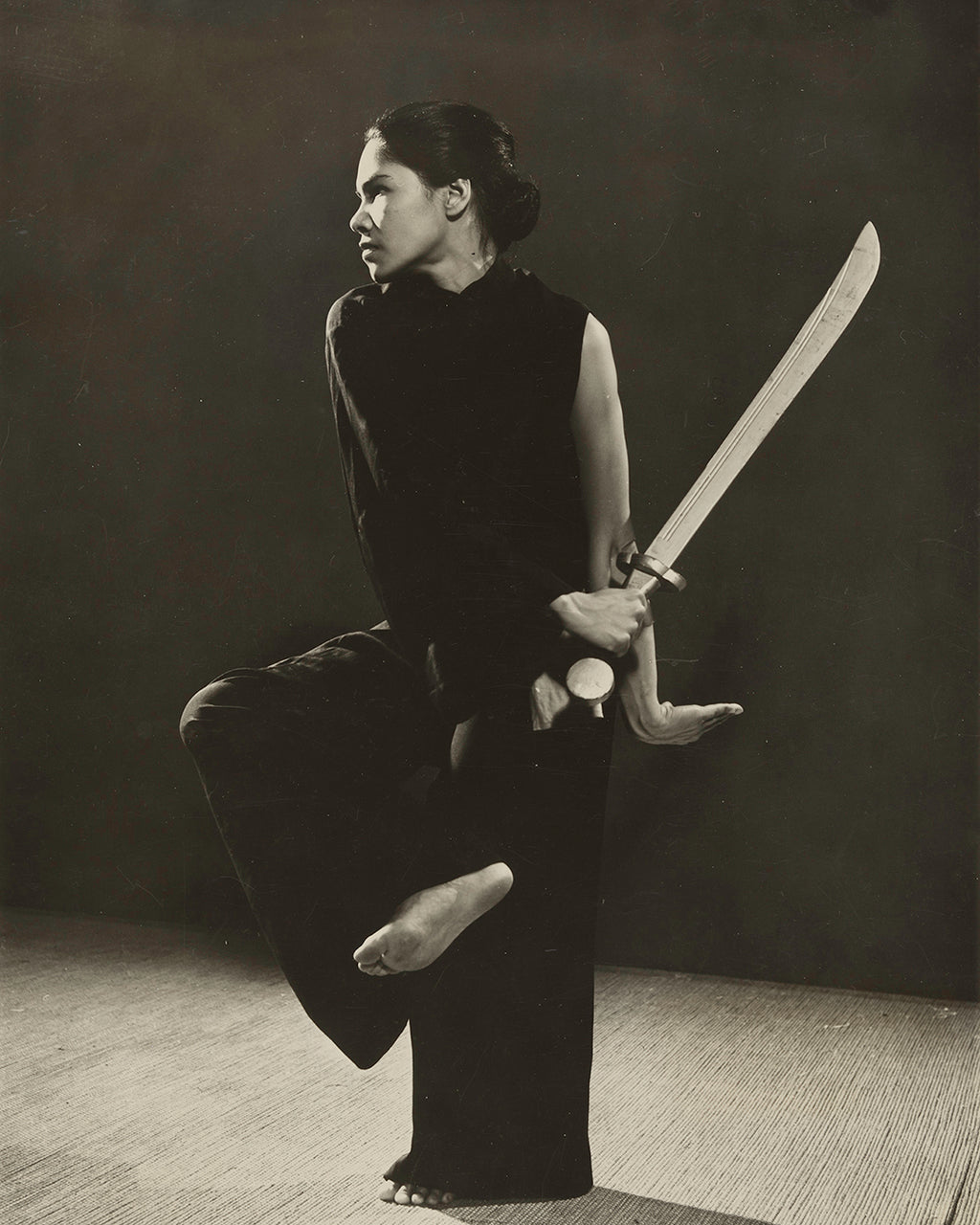

The New York Public Library for the Performing Arts’ current exhibition is a dance epic. Full of tragedy and triumph spanning centuries and the globe, “Border Crossings: Exile and American Modern Dance 1900 – 1955” recenters the story of modern dance around historically marginalized artists often left out of the modern dance canon.

“This show is about re-reading modernism through trauma and alienation, and to understand modernism not as this unified canonical narrative, but in fact a constant series of breakages, resistances, ruptures, and traumas,” Dr. Bruce Robertson said. Robertson is co-curator of “Border Crossings” with colleague Dr. Ninotchka Bennahum.

Dresses, domestic chores, grief. A community of women more feral than feminine. Five performers wear a changing selection of 40 dresses that serve as both costume and prop.

Continua a leggerePossibly one of Los Angeles’ best kept terpsichorean secrets, artistic director, choreographer, and teacher Josie Walsh has decidedly forged a path unlike any other.

Continua a leggereThe legacy of George Balanchine will be forever entwined with the enduring fiefdoms he established, the School of American Ballet and the New York City Ballet.

Continua a leggereOf the many stylish touches in Scottish Ballet’s “Mary, Queen of Scots,” the titular Tudor’s black pointe shoes are my favourite.

Continua a leggere

comments