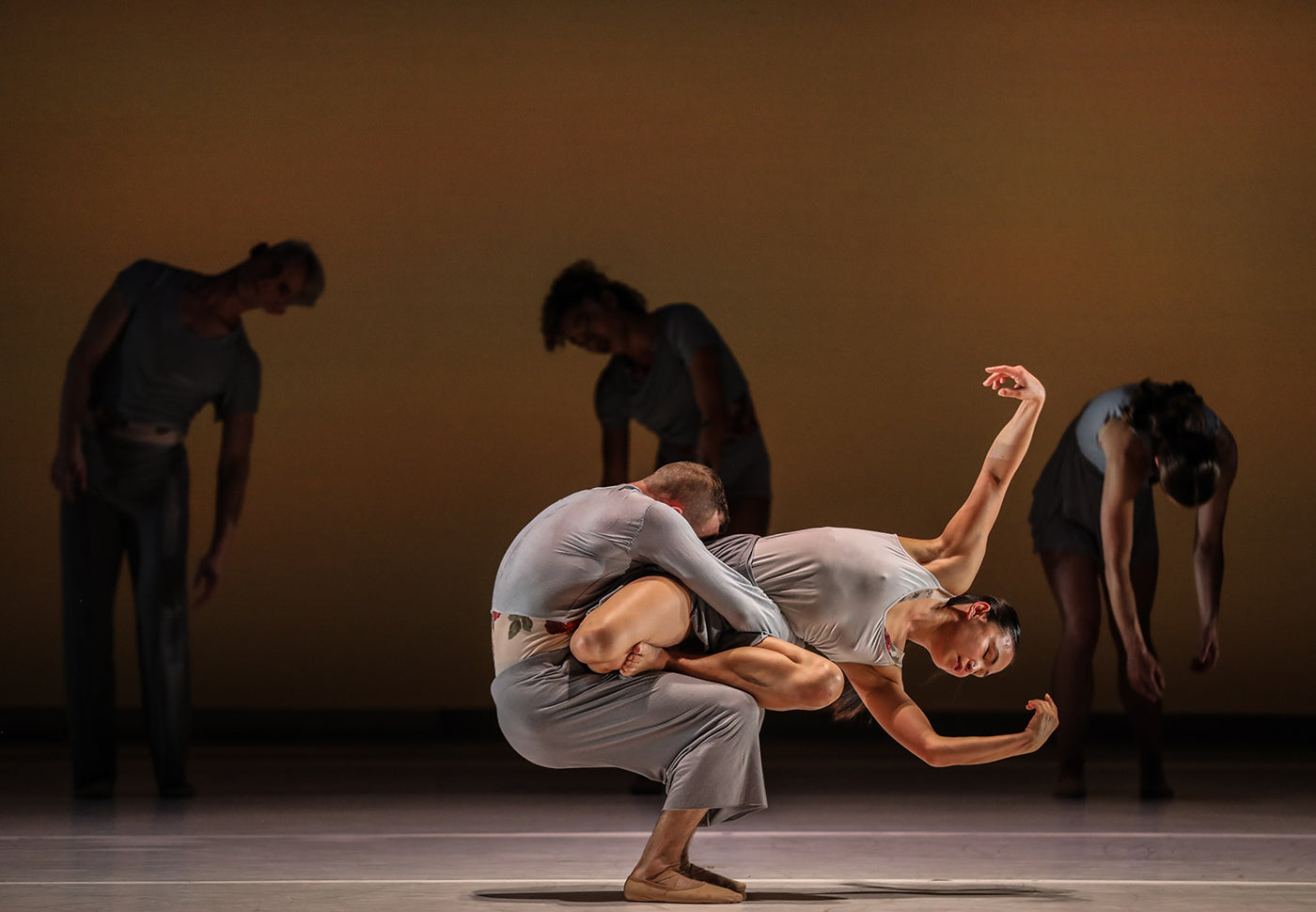

Russian-born Lobsanova joined the National Ballet of Canada in 2004, becoming principal dancer in 2015. But this week, she plays another part, revealing another incarnation of her artistic self, presenting her first choreography, “3[4],” as part of “Five Creations,” an evening of new work developed within the National Ballet's two-year Choreographic Workshop.

The workshop, lead by the National Ballet's choreographic associate Robert Binet, is designed to encourage new choreographic voices, and to give opportunities to dancers to create. Bringing together choreographers from outside the company, as well as dancers, Binet says, “it sits a little outside the usual workings of the company.”

Binet, together with Toronto-based contemporary dance luminaries Peggy Baker and Laurence Lemieux, acting as choreographic mentors, organised the workshop into two phases.

“The format has recently changed to extend over a longer period,” Binet explained in a recent phone call, “to give ten choreographers, seven of those from within the National Ballet, a chance to develop work in two phases.” For the second phase, Binet with Baker and Lemieux selected five works to progress to the stage. Presenting work alongside Lobsanovaare first soloists Brendan Saye and Robert Stephen, and independent choreographers Hanna Kiel and Alysa Pires.

Speaking on a recent Sunday afternoon, Lobsanova explained her inspiration and process in creating “3[4]:” “3[4] refers to the three and a half segments—well it's four, but the last is just the music and lighting.” You could, of course, read the time signature 3/4 in there, and even perhaps the relationship, three quarters.

Each movement is distinct from the other, she notes, adding, “humanity is the connection, as a broad concept.” Within the umbrella of humanity are three distinct themes, and deeply human stories.

“The first piece is based very loosely on a homily I heard. It was a speech given by a monk in the 50s, and talking about a time when he was a doctor in Switzerland. He was talking about an incident where he spent 10 hours with a patient who was schizophrenic and was in a coma.

“With the ten hours, with nothing but his attentiveness, the patient woke up.

“Just the mere idea of spending time with somebody, and how far that goes without any other influence—even if the patient was medicated, and facilitated with everything that he needed—just the extra push of somebody being present, and the value of the presence of being with someone who is ill.”

“I wanted to illustrate that in whatever way I could,” Lobsanova explained, with the inspiration directing her “into a story line of one dancer starting the piece, and another meeting them later on. One dancer touches the other's foot, and she starts moving, and then touches the hand, and she stops. Within the sequence, they repeat it three times, and switch roles, of someone being the sick person, and someone being the guest.”

The second movement is no less profound, taking for its jumping-off point Sophocles' riddle of the Sphinx.

“What creature goes on four feet in the morning, two at noon, three in the evening...and none at night... The less feet it may rely on the wiser it becomes."

“The answer, of course, is man.

“They are dancing the chronology of the life of people, through that literal image of crawling, and on two feet, then with a cane, and then dead. I have them literally on four, two and then, three, being each other's cane,” Lobsanova describes the sequence. “Then it reverses—kind of like Benjamin Button to meet in the middle, as one another's guides.” Set to Arvo Pärt's “Spiegel Im Spiegel” she corners another literal note, in how the movement mirrors the riddle.

“The third theme is deafness, and the deaf community. My grandparents were deaf, and I've always wanted to do something for them.” Titled “Ode to Beethoven and others,” the dance is set to Beethoven's 9th Symphony, “right before Ode to Joy.”

“I wanted to incorporate his strongest music that we know, and the music that he created when he was in his most deaf state.”

Stephanie Hutchison, principal character artist with the National Ballet, dances a solo in silence, garbed in a “plastic dress—it symbolises being hindered. She's carving out the word ’deaf‘ with her arms. She moves from a pool of light, and she starts finding her legs, and carving out the word ‘love.’

“I wanted to find a word that was an all encompassing resolution, which is basically love. So that becomes the denouement of her solo, writing love, finding her voice with her whole body,” leaving the light and music to continue dancing—“The light and the music (the things in the mind that are not seen or heard),” taken from her notes.

Spirituality, too, is a thread linking the pieces, and a guide for Lobsanova. “I couldn't really live without it," she says.

Dancing alongside Hutchison are three thrilling new additions to the company, corps dancers Siphe November and Chae Eun Yang, and apprentice Hannah Galway. Not entirely offstage, Lobsanova can be seen dancing in Saye's work for “Five Creations.”

comments